|

Aviate,

Navigate, Communicate -- in that order.

|

On

July 2, 1937 at 0000 GCT, the Lockheed Electra Model

10E began its take-off roll at Lae, New Guinea.

It was the beginning of a tragic flight and the

biggest aviation mystery in history. The

over-water flight of 2,556 miles along the Equator to

Howland Island would place extreme demands on all

navigation resources and skills of that time.

The navigator for the round-the-world

adventure was arguably the best in the world, Fred

Noonan. Nevertheless, the successful conclusion

of the flight could be assured only by RDF --

Radio Direction Finding (see Live

Reckoning) performed by the Pilot-in-Command,

Amelia Earhart. On

July 2, 1937 at 0000 GCT, the Lockheed Electra Model

10E began its take-off roll at Lae, New Guinea.

It was the beginning of a tragic flight and the

biggest aviation mystery in history. The

over-water flight of 2,556 miles along the Equator to

Howland Island would place extreme demands on all

navigation resources and skills of that time.

The navigator for the round-the-world

adventure was arguably the best in the world, Fred

Noonan. Nevertheless, the successful conclusion

of the flight could be assured only by RDF --

Radio Direction Finding (see Live

Reckoning) performed by the Pilot-in-Command,

Amelia Earhart.

Aviating,

Navigating, Communicating (in that order)

Piloting requires multitasking

aloft. Each task has its own primacy; each is a sine qua

non for the successful completion of every

flight. Contrary to the simplistic mandate

cited above, priorities must change with the various

phases of flight.

Thus, during take-off and

early stages of climb-out, the pilot will be focused

most intensely on Aviating (see

Pilot's Nightmare).

Same during the final stages of approach and landing

(see Sloping in the Dark).

In between, often for hours-on-end, Navigating takes

first priority, as satirized in one definition,

"Latitude is where we are lost, and Longitude

is how long we have been lost there."

So it would seem that Communicating should belong as the

lowest

priority. "Never drop the plane to fly the

microphone," goes an old saying.

Still, are there occasions when Communicating must take

center stage? Indeed yes, when radio operations

become essential for Navigating.

Nota bene, the principles of RDF have not changed

over the decades, only the radio technologies.

There are two modes...

Receive-Only RDF ~~~ To establish a course

directly toward Howland Island, Amelia

Earhart would need to operate an RDF

antenna, which is the loop being displayed

on the right and visible as it was mounted

atop the Electra in the photograph above.

With an appropriately tuned radio receiver,

she would be able to rotate the loop to "get

a minimum" signal and thereby determine the

direction from which a radio signal is being

transmitted. Using that bearing

angle, the Electra would be turned to take

up a heading

directly toward the source. In this

mode, airborne RDF equipment operates

"receive-only" -- simplex

in radio parlance. However... Receive-Only RDF ~~~ To establish a course

directly toward Howland Island, Amelia

Earhart would need to operate an RDF

antenna, which is the loop being displayed

on the right and visible as it was mounted

atop the Electra in the photograph above.

With an appropriately tuned radio receiver,

she would be able to rotate the loop to "get

a minimum" signal and thereby determine the

direction from which a radio signal is being

transmitted. Using that bearing

angle, the Electra would be turned to take

up a heading

directly toward the source. In this

mode, airborne RDF equipment operates

"receive-only" -- simplex

in radio parlance. However...

In 1937, no permanent

radio beacon

was installed on Howland. Such a

facility would be transmitting an

identification signal continuously on a

dedicated frequency identified by Morse

Code. Instead,

the US Coast Guard cutter Itasca

had been positioned at anchor offshore

Howland to support RDF for the Earhart

flight. A qualified radio operator

on board Itasca was supposed to

broadcast an improvised homing

signal in compliance with a time-of-day schedule

on an assigned frequency, with

station identification to be

recognizable by Amelia Earhart -- all by

protocols coordinated in advance of the

inbound flight.

Half-Duplex RDF ~~~ For guidance from the

ground ('DF

steer'), two-way communications had to

be established with USCG Itasca,

which is shown on the right.

Communications were to take place by voice

or by Morse Code on assigned

frequencies. Amelia Earhart would then

be requested over the radio to transmit a

steady signal long enough for the Itasca

radio operator to ascertain the direction of

the source in the sky using a loop antenna

on the ship. Having obtained the bearing

to the Electra relative to the ship's

heading, the operator must compute the

appropriate compass direction for the

Electra to fly and transmit that information

to Amelia Earhart as a heading

by voice or Morse code. All of that

takes time, of course, and all the while,

the Electra would be flying at over a

hundred miles per hour on an uncorrected

heading. Half-Duplex RDF ~~~ For guidance from the

ground ('DF

steer'), two-way communications had to

be established with USCG Itasca,

which is shown on the right.

Communications were to take place by voice

or by Morse Code on assigned

frequencies. Amelia Earhart would then

be requested over the radio to transmit a

steady signal long enough for the Itasca

radio operator to ascertain the direction of

the source in the sky using a loop antenna

on the ship. Having obtained the bearing

to the Electra relative to the ship's

heading, the operator must compute the

appropriate compass direction for the

Electra to fly and transmit that information

to Amelia Earhart as a heading

by voice or Morse code. All of that

takes time, of course, and all the while,

the Electra would be flying at over a

hundred miles per hour on an uncorrected

heading.

In concept, Half-Duplex RDF

operates as a reciprocating, two-way, simplex

system -- half-duplex

in radio parlance. By the way,

wireless telephony, which we take for

granted today, supports what is called full

duplex communications, with

transmitting and receiving going on in

both directions simultaneously. Full

duplex is still not found in radio

equipment on even the most complex

airliners of the Twenty-First Century.

|

As readily seen in the descriptions

above, for RDF to be successful in either mode,

equipment and people on the ground and in the sky must

all be in good working order and coordinated.

Last Words of

Amelia Earhart

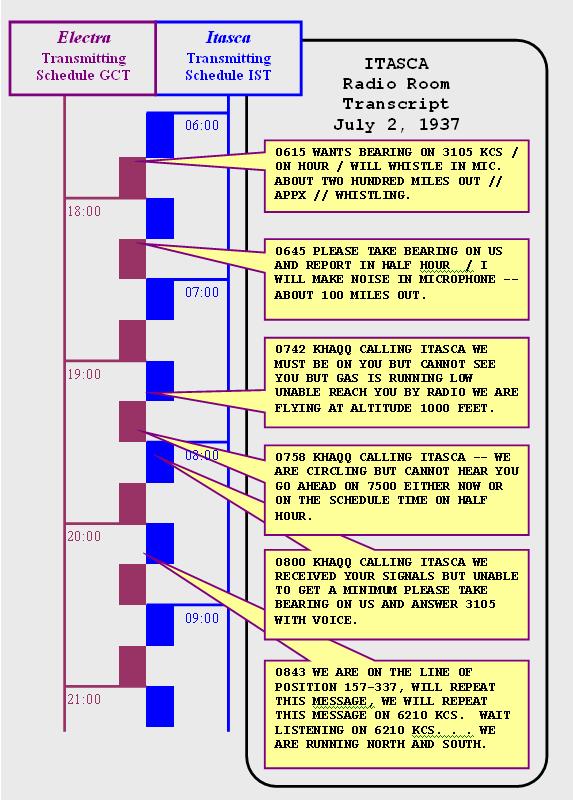

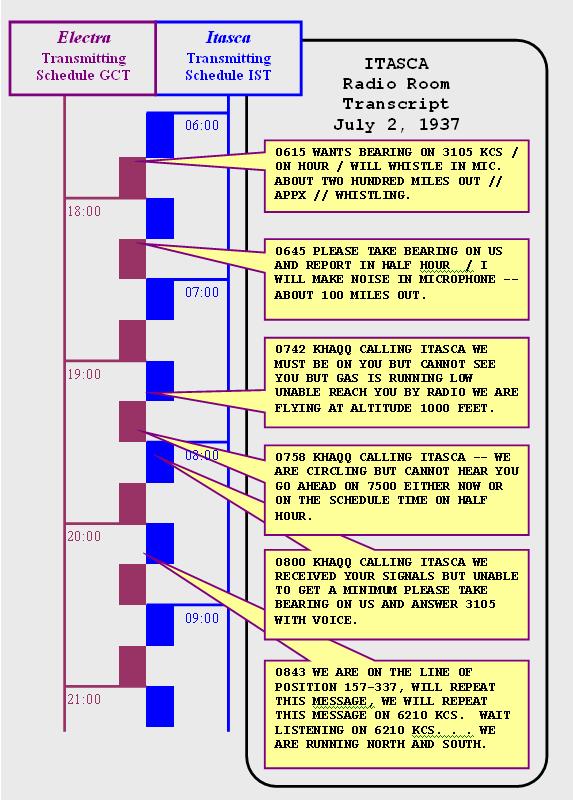

The figure below is based on

transcriptions from the radio room aboard the USCG Itasca

standing by Howland Island on July 2, 1937.

These are the last six radio messages received from

Amelia Earhart over a period of two-and-a-half hours

on that fateful day.

The pre-arranged 'radio schedule'

comprises 'time-slots' during which Earhart was

supposed to transmit simplex at quarter-to and

quarter-passed each hour In between, Itasca

was supposed to transmit simplex on the hour

and the half-hour.

Historians

have

taken special notice of the potential for confusion

resulting from two time-zones: Earhart and Noonan

operated on Greenwich Civil Time (GCT)

while the Itasca clocks were all set on local

time at Howland ("IST" for 'Itasca Standard

Time'), such that IST

= GCT minus

11:30. A source of confusion for sure, but

if everybody stuck to the script, those time-slot

assignments ought to have worked just fine in

half-duplex. Historians

have

taken special notice of the potential for confusion

resulting from two time-zones: Earhart and Noonan

operated on Greenwich Civil Time (GCT)

while the Itasca clocks were all set on local

time at Howland ("IST" for 'Itasca Standard

Time'), such that IST

= GCT minus

11:30. A source of confusion for sure, but

if everybody stuck to the script, those time-slot

assignments ought to have worked just fine in

half-duplex.

Sophisticated solvers will immediately

observe the following worrisome problems:

- Three different radio frequencies

being called out by Amelia Earhart: 3105, 6210, and

7500 Kcps (thousands of cycles per second, "Hz"

in today's terminology).

- Three different forms of

modulation: "noise," "voice," "whistling" -- but

not "code" (neither Amelia Earhart nor Fred

Noonan understood Morse

Code).

For the many technical issues and facts

beyond those appropriated for Simplexity

Aloft, there can be no doubt that the most

comprehensive reference in all of Amelianna

is the fascinating e-book entitled Amelia Earhart’s

Radio: Why She Disappeared by Paul Rafford,

Jr.

Complexity

trumped simplicity for Amelia Earhart and Fred

Noonan that day, hence the appropriation of "simplexity"

in the title of this puzzle. As the Electra

approached the end of its final flight, a lot could

go wrong. And apparently did.

|

How

many critical issues can you

identify by parsing the last words of

Amelia Earhart?

|

GO TO SOLUTION

PAGE

|

On

July 2, 1937 at 0000 GCT, the Lockheed Electra Model

10E began its take-off roll at Lae, New Guinea.

It was the beginning of a tragic flight and the

biggest aviation mystery in history. The

over-water flight of 2,556 miles along the Equator to

Howland Island would place extreme demands on all

navigation resources and skills of that time.

The navigator for the

On

July 2, 1937 at 0000 GCT, the Lockheed Electra Model

10E began its take-off roll at Lae, New Guinea.

It was the beginning of a tragic flight and the

biggest aviation mystery in history. The

over-water flight of 2,556 miles along the Equator to

Howland Island would place extreme demands on all

navigation resources and skills of that time.

The navigator for the

Receive-Only RDF ~~~ To establish a

Receive-Only RDF ~~~ To establish a  Half-Duplex RDF ~~~ For guidance from the

ground ('

Half-Duplex RDF ~~~ For guidance from the

ground ('