If human beings were

intended to fly, The Intelligent Designer would

have made their poop white.

-- Paul

Niquette

Diagram obtained under Fair-Use

from StartFlyingRC.

AGL

(Altitude) Above Ground Level, where all aircraft

must fly. Always a positive number, by the way.

Distinguished from MSL, (above)

Mean Sea Level, which is what an altimeter measures,

and can indeed be negative. Cloud levels are given

as AGL.

When in doubt, hold your

altitude. No one has ever collided with the

sky.

-- Old

Aviation Saying

| In 1980, a friend of mine

set one of aviation's lesser known world

records: Low-Altitude Endurance, flying at

-200 feet MSL (+50 feet AGL) for over five

hours, in Death Valley (now her husband

plans to set the high-altitude submarine

record with a one-man submersible in Peru's

Lake Titicaca).

To determine altitude AGL

-- the most vital measurement aloft -- the

pilot must know: (a) the plane's altitude

MSL, (b) the plane's geographical

position, and (c) the elevation (MSL) of the ground (the

G in AGL) at that location.

|

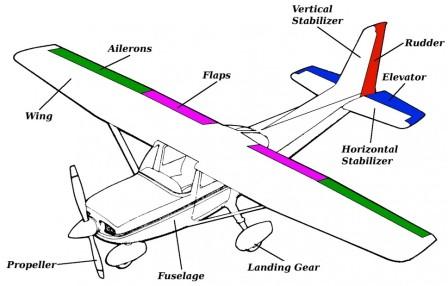

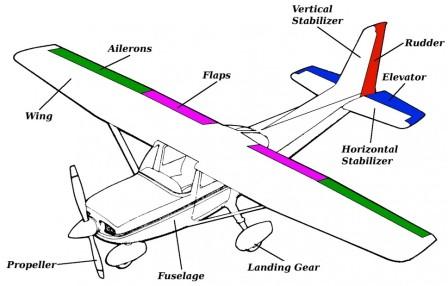

aileron Movable

surface on the outboard trailing edge of each wing.

Operated by rotating the control wheel (or tilting

the stick from side to side), the ailerons control roll (animation).

Aileron is one of the few pure

aviation terms and was derived from the diminutive

form of the French aile (wing). Other French

contributions: empennage,

fuselage, and longeron.

airspeed

The speed at which the airplane moves through the air

expressed in knots

(kts nautical miles per hour). airspeed

The speed at which the airplane moves through the air

expressed in knots

(kts nautical miles per hour).

Airspeed is distinguished from groundspeed and comes in

two forms: 'Indicated airspeed' (IAS),

corrected for altitude and temperature, becomes

'true airspeed' (TAS). Thus "truing

out" at 150 KTAS with

a 15-knot tailwind "makes good" 165 knots "over the

ground."

| In early days of aviation,

airspeeds were expressed in mph (statute

miles per hour) same as

automobiles and trains. Marketing

psychology doubtless played a role: To say

your sedan goes "100 mph" is more exciting

than "87 kts" -- much as $100 is preferred

for a prize, while $99.95 works better as a

price.

Back in 1937, for one

flight of 2,228 nm (2,566 sm),

confusion about kts and mph for winds aloft

may have participated in tragedy (see Which

Way, Amelia?).

|

Airspeed, altitude and

brains: any two out of the three are needed to

complete the flight successfully.

-- Old Aviation Saying

alphabet, phonetic

Alpha, Bravo, Charlie (shar-lee), Delta,

Echo, Foxtrot (often shortened to Fox), Golf, Hotel,

India, Juliet, Kilo, Lima (pronounced as the city not

the bean), Mike, November, Oscar (oss-kah), Papa,

Quebec (kay-beck), Romeo, Sierra, Tango, Uniform

(oo-nee-form), Victor (vik-tah), Whiskey, X-ray,

Yankee, Zulu.

Use these in casual conversation

anywhere in the world and pilots will reveal

themselves by asking, "What are you flying?"

Never drop the airplane to fly

the microphone.

altimeter An instrument

that measures air pressure, like a barometer.

See MSL.

The face is calibrated in

'feet MSL' and an adjustment ("Kollsman Window")

that enables correcting for local atmospheric

pressure, which is in turn given as 'inches of

mercury' (29.92 being the so-call "Standard

Atmosphere"). Clear?

Radar altimeters measure altitude

above ground level AGL

directly but are extremely rare in light aircraft;

they will doubtless become more common with the

growth of the VLJ fleet.

altitude

Three entries: Above

Ground Level , Above

Mean Sea Level, Density Altitude.

angle-of-attack

The angle between the chord of the wing and the

relative wind (also called angle-of-incidence).

| The chord is simply the

straight line that connects the leading edge

of the wing with the trailing edge (longest

dimension front-to-back). The relative wind,

not so simply, is the direction from which

the air appears to be coming. In level

flight, the relative wind strikes the plane

horizontally from straight ahead. During

ascent (or descent), the relative wind comes

from above (or below) the plane. |

AOPA Aircraft Owners and Pilots

Association, non-profit political organization

serving the interests of its members to promote

the economy, safety, utility, and popularity of

flight in general

aviation aircraft.

Area Rule An ironic

aerodynamic property for minimizing drag

in high-speed aircraft.

| Discovered back to the

fifties, the rule mandates a constant

crossectional area as measured at stations

along the center-line of the aircraft.

Thus the fuselage on some aircraft

accommodates the wings by virtue of

"coke-bottle" design.

As the VLJ

segment of General

Aviation fleet becomes prominent,

private pilots can expect increased

pertinence for jet-age lingo, like "thrust

lever," "engine pressure ratio," "turbine

stall," "flame-out," and "after-burner"

("reheat" in UK parlance).

|

Artificial

Horizon or

Attitude Indicator, an instrument symbolizing the

aircraft in the center, and the background

controlled by a gyro. Artificial

Horizon or

Attitude Indicator, an instrument symbolizing the

aircraft in the center, and the background

controlled by a gyro.

Depicted

on the right is an artificial horizon in the panel

of an aircraft that is momentarily pitching up 5 degrees and rolling right by 15 degrees.

ATC Air

Traffic Control, a service of the FAA (Federal

Aviation Administration) in which air traffic

controllers are responsible to guide and protect

airplanes (see traffic).

| Most people are familiar

with control towers. The 'tower' operators

(also called 'local' controllers) are

responsible for planes in the process of

landing and taking off. 'Ground control'

directs planes on the ground. Movie-makers

take note: you never call ground control

while in the air. At the radar scopes you

have 'departure' controllers, 'enroute'

controllers, and 'approach' controllers.

The vast majority of

airports do not have control towers. Most

use Unicom or CTAF

(Common Traffic Advisory Frequency) to

exchange information among the pilots

flying in the pattern. Works fine, by the

way. ("Caldwell traffic, Cardinal Niner

One Four, wing-up, turning right base for Runway

Three Zero, behind the Cherokee.")

|

ATIS Automatic

Terminal Information Service (pronounced ATE-is), a

transcribed radio message that gives up-to-date

advisories about conditions and procedures at a

particular airport. The pilot listens to the message

on the ground before taxiing and in the air before

approaching the airport.

| "Torrance Airport,

Information Juliet, zero-two-zero-zero Zulu.

Weather: sky partially obscured, two

thousand scattered, two-five thousand

broken. Visibility: five, haze. Wind:

two-seven-zero at one-five. ILS Two-Niner

Right approach in use, landing and

departure: Runways Two-Niner Right and

Two-Niner Left. Caution equipment in use on

taxiway kilo. Advise on initial contact, you

have received Information Juliet." |

attitudes,

unusual In aviation, the expression

'unusual attitudes' has a special meaning. Just so

you know, it has nothing to do with extraordinary

mental states or peculiar dispositions. 'Attitude'

is the general term used to describe (ahem) the

instantaneous angular position of the airplane with

respect to the horizon.

| Attitude is a vital thing

for the pilot to know -- which way is up? --

and to control. The task is made easy when

you can see the horizon out the window,

difficult -- hard! -- when you cannot.

Straight and level flight is one of the most

common -- 'usual' -- attitudes, as are

climbing, descending, and coordinated

turns.

So then, what is an

'unusual' attitude? It is any attitude not

required for the normal conduct of flight.

Unintentional attitude is more to

the point.

Airplanes tend to

'over-bank' constantly. Here's why. Say a

slight disturbance lifts the right wing.

Suppose that, through momentary pilot

inattention, it is not immediately

corrected. A left turn ensues. That might

not be especially inconvenient -- if you

happen to desire a left turn. Inadvertent,

though, and you have an unusual attitude.

Over-banking results from

the turn itself. Intended or not, while

flying in a curving path the outside wing

has farther to go than the inside wing.

For the case under consideration, that

means the right wing is traveling faster

than the left wing, and develops more lift

-- rolling your plane more steeply to the

left. The motion can be exceedingly

subtle. You are not likely to feel it.

Most likely, though, the

pilot is the problem. Carelessness in

cross-checking the instruments and errors

of interpretation, confusion and

disorientation, lack of training or being

out of practice -- these are among the

foibles that beset the person at the

controls.

Unusual attitudes are not

really so unusual. Safety dictates that

you must learn how to recover from them,

which often requires dealing with vertigo.

|

Mankind has a perfect record in aviation; We

never left one up there yet.

-- Old

Aviation Saying

autopilot Airborne

electronic equipment that automatically actuate the

controls of an airplane.

The simplest is called a 'wing

leveler,' which is capable merely of 'roll-hold.' You might add 'heading-hold,' 'pitch-hold,' and

'altitude-hold.' Finally, there is the

'coupler', which connects the autopilot to your navigation system. Then you

might ask yourself why you ever took up flying.

avigation an aviation neologism (see navigation).

The

sky, to an even greater extent than the sea, is

terribly unforgiving of errors.

--

Old Aviation Saying

AvWeb Web-based,

independent aviation news resource.

azimuth Angle

measured between some reference line, generally north (either magnetic or true)

and a fix or a target (in radar). If the

reference line is the longitudinal axis of the

aircraft, the preferred term is bearing.

bank Same as roll. 'Angle-of-bank' is that

which the wings momentarily make with the horizon.

In 'coordinated turns' (neither slipping nor skidding),

best to think of your fanny as 'down' and what you

see through the plexiglass as a crooked picture on

the wall.

balance See weight-and-balance.

base leg

See pattern.

beacon Coded signal,

either a rotating light (atop an obstacle or an

airport tower) or a navigational radio (most often

called an NDB for

"non-directional beacon").

At a civilian airport the

light signal alternates between green and white; for

military aerodromes, the beacon appears to flash

green-white-white.

Radio beacons are suitable for direct

inbound navigation (homing)

or for taking cross-bearings;

they are subject to errors in outbound navigation

(see ADF).

bearing An angle measured clockwise relative

to some reference, often the longitudinal axis of

the airplane (see numbers)

or from North (see omni).

Best Angle of Climb Indicated airspeed

(abbreviated "V X" in V-speeds)

that enables the aircraft to ascend in altitude at

the steepest angle (minimum distance), most

relevant for clearing obstacles, distinguished

from -- and slower than -- Best

Rate of Climb speed.

Best Rate of Climb Indicated airspeed

(abbreviated "V Y" in V-speeds)

that enables the aircraft to ascend in altitude at

the fastest rate (minimum time), most relevant for

minimizing time enroute, distinguished from -- and

faster than -- Best Angle

of Climb speed.

blip The spot on the

radar screen corresponding to the echo of an

airplane, also called 'target' (see transponder). Maybe blip

sounds like what a spot looks like.

CAP Civil Air Patrol,

a civilian auxiliary of the United

States

Airforce.

CAVU Ceiling And

Visibility Unlimited, colloquially 'severe clear.'

The extreme opposite of WOXOF, "indefinite ceiling

zero, sky obscured, visibility zero with fog"

(decoded from old fashioned weather teletypes).

ceiling A broken or

overcast cloud layer at some measured elevation AGL.

For landing an aircraft, the pilot

must have some prescribed forward visibility, often

a mile, under a ceiling of at least a few hundred

feet. These are the so-called 'landing minimums',

and they vary from airport to airport.

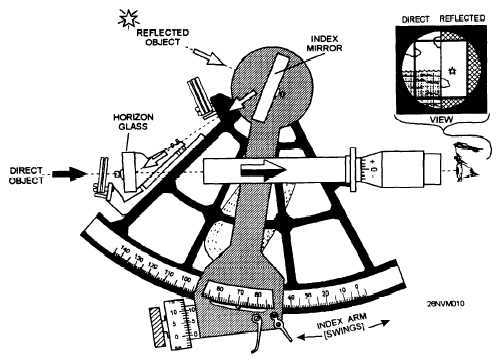

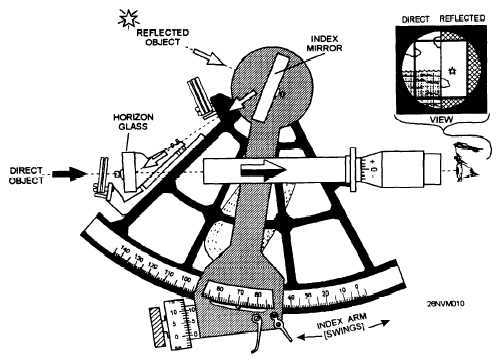

celestial navigation

Nautical procedure appropriated by commercial and

military aviation in bygone days for finding position

based on angular measurements of sun, moon, and stars

(more at sextant).

checklist

An ordered set of references to procedures vital to

the safe conduct of flight. Checklists are

customarily printed on laminated pages bound into a

notebook immediately accessible to the pilot in

command.

| A given checklist pertains

to a specific phase of flight:

Pre-Flight Inspection,

Before-Starting-Engine, Pre-Taxi,

Pre-Take-Off, Approach-to-Landing,..

Emergencies (by type).

Every item on a checklist

has two parts, the first in the form of a

noun phrase called the “challenge,” for

each of which a “response” is

mandated: "Flaps -- Set"; “Landing

Gear – Down and Locked, Three-Greens

Showing”; "Mixture -- Full

Rich."

A checklist does not tell

the pilot how to perform the

procedure. Technical manuals and

flight training are supposed to do that.

Aviation mnemonics are

commonly used as informal checklists

(CIGAR, GUMP, CCCC, TTTTT), with varying

degrees of effectiveness.

|

A checklist is not a

do-list.

– Old

Aviation Saying

chronometer A precise

time piece used in navigation.

Illustrated above is an

especially fancy one, perched for the night atop an

E6B computer. You see

plenty of bezels and buttons plus an auxiliary

movement for GMT. Given

the indicated settings, the pilot must be slumbering

in which time zone?

| Time waits for no one.

Whoever first sang

those words might have been thinking of

aviation, where passing the middle marker on

the ILS requires reading

the chronometer immediately in order to

declare a 'missed approach' when the time

comes.

Nota bene, celestial

navigation experiences a full mile

of shift in longitude at the equator with

every 3.5 seconds of error in time

measurement.

|

CIGAR An abbreviated

pre-take-off checklist: Controls (free and correct),

Instruments (heading, altimeter, horizon), Gas (fuel

selector on fullest tank), Attitude (trim),

Run-up (testing of the engine prior to take-off).

| The least useful acronyms

are those which provide no mnemonic support

for sequence: TTTTT (Time, Turn,

Throttle, Tune, Talk) for the five things

you are supposed to do at the outer marker

(which I have replaced with "watchman power

and radio chatter"); for emergencies, I

replaced the traditional CCCC

(Climb, Confess, Communicate, Comply) with

my on credo: PADO (Pull-up, Admit that I

need help, Describe my predicament, Obey

instructions). |

Aviate, Avigate,

Communicate -- in that order.

-- Not so old aviation saying.

clearance Loosely

speaking, an agreement between ATC

and the pilot of an aircraft, under the terms of which

safe separation from other aircraft is assured in the

event of communications failure. Simple clearances

include permission to taxi somewhere on the airport,

to take off, to land, to change frequencies.

| Under IFR,

a clearance covers a chain of in-flight

procedures, which must be taken down by the

pilot in "aviation shorthand" from clearance delivery and

read back verbatim. Here is an

example: C34914 CLRD TO SFO M3 EXP H IN

5MIN. MRH TO X SLB R123, RT 270, RV TO

LAX VOR. FPR. DEP 126.4,

SQ3241. Which sounds like this over

the radio…

"ATC Clears Cardinal Three

Four Niner One Four to the Santa Francisco

Airport. Maintain three thousand. Expect

higher five minutes after departure.

Maintain runway heading until crossing the

Seal Beach one-two-three degree radial,

right turn heading two-seven-zero for

radar vectors to Los Angeles VOR. Flight

plan route. Contact Departure Control,

126.4. Squawk 3241. Proceed with your

readback."

|

cockpit Where you

control a plane from, which everybody knows. With

the increasing presence of women in flight crews,

the term is being displaced by 'flight deck.'

As with other terms ('navigate,' 'dead

reckoning,' 'rudder'),

'cockpit' came to aviation by way of maritime

parlance, there being a lower space near the stern

from whence some vessels are steered. Just so there

is no misunderstanding, 'cock' derives originally

from the fighting bird.

cockpit, glass Collection of flat-screen,

twenty-first century displays. Prepare to learn a

whole new collection of TLDs,

including FMS, SVS,

and PFD.

compass

A

primitive instrument that indicates magnetic

heading. It has digits painted around a black

cylinder that floats in a bath of mineral oil.

The thing is subject to many kinds of errors as the

plane maneuvers -- so much so, that a pilot must

rely instead on his or her "heading indicator,"

which is stabilized by a gyro. compass

A

primitive instrument that indicates magnetic

heading. It has digits painted around a black

cylinder that floats in a bath of mineral oil.

The thing is subject to many kinds of errors as the

plane maneuvers -- so much so, that a pilot must

rely instead on his or her "heading indicator,"

which is stabilized by a gyro.

Both instruments are subject

to the same design flaw. The designer was

obviously ignorant of human factors and suffered a

misguided penchant for abbrev.

| For safety's sake,

headings are invariably given over the

radio as three digits. That's called

'redundancy.'

Thus,

North-West is said,

"three-zero-zero." On both compass

and heading indicator, the least

significant digit is deleted on

every printed number, such that North West

reads "30." That's bad enough,

but then leading zeroes are also

deleted (must be to save paint).

That means North-East, which is said

"zero-three-zero," reads just plain

"3." Now, 30 is exactly 270 degrees

from 300, making the expression "right

angle" a potentially fatal -- well, misnomer.

And yes, a high-time pilot I know

personally has experienced the indicated

inadvertence while aloft in IMC. |

course Intended

direction of flight -- usually referenced to magnetic

North, some place up in Canada where compasses point.

Because of wind, your course generally differs from

your heading.

crab Angle between course and heading

resulting from the influence of a crosswind

component.

Crab is especially onerous on landing.

The pilot uses an intentional (side) slip to correct it out; otherwise

the wheels will not be lined up with the runway at

the instant of touchdown.

crosswind landing,

crosswind takeoff Runways are generally

designed to be lined up with the wind. Once the

airport is built, though, it doesn't always work out

that way.

| If a significant component

of the wind is blowing across the runway,

an airplane taking off tends to skid

sideways just as the wheels leave the

ground. For a crosswind take-off,

the pilot anticipates this tendency by

prepositioning the aileron

control for a turn into the wind before

releasing the brakes. Immediately

after take-off the plane actually does

turn into the wind and then commences to crab along the runway.

Best to explain these matters to your

passengers before starting the engine(s).

Crosswind landings have

the same problem in reverse, but not

the same solution. The preferred

approach is to execute an intentional slip by banking into

the wind and holding opposite rudder to cancel

out the effect of the crosswind and to

keep the plane's landing gear lined up

with the runway. Of course, with

the plane banked, one wheel will

touch-down first, but -- hey, nobody

ever said crosswind landings have to be

pretty.

|

Flying is the second-most

thrilling experience in life; the first is

landing.

crosswind leg

See pattern.

cruise-climb Conventional

maneuver in the early stages of each flight, using

the indicated airspeed

recommended in the owner's manual for the

aircraft, calling for a pitch angle that affords

good forward visibility and an air-flow that assures

good engine cooling, distinguished from -- and

faster than -- Best Angle of

Climb speed and Best

Rate of Climb speed. The abbreviation "V CC"

in the V-Speeds is a

coinage for this glossary.

CUT Coordinated

Universal Time (see GMT.).

curve, power See drag.

dead reckoning

An unclever contraction of 'deductive reckoning,'

which uses speed and direction together with elapsed

time to estimate one's present whereabouts from some

previously known position. In aviation, the

procedure is especially prone to errors, primarily

because of winds, but it's anything but

"dead."

The preferred term is pilotage. Likewise, the

phrase 'positioning flight' seems to have replaced

'dead-head' in aviation parlance.

| There is some controversy

about the derivation of the phrase.

According to the Oxford English

Dictionary, the 'dead reckoning'

dates from Elizabethan times

(1605-1615). The popular etymology

cited here is not documented in

any historical dictionary. Instead,

'dead reckoning' is navigation without

celestial references. Whereas with stellar

observation, you are, in some sense, live

-- working with the stars and the movement

of the planets. Conversely, using

mere compasses and clocks but no sky, you

are working dead. |

delivery,

clearance A position in the control

tower responsible to obtain the authorized

procedures for each flight under IFR

and to provide them as an official clearance to the pilot over

a dedicated radio frequency.

density altitude

An aviation expression used to

describe the effects three factors that determine

the local density of the air.

The three H's are invoked as a

mnemonic: HHH for High,

Hot, and Humid. That adds up to

'high density-altitude' -- a perilously poor

term. It really means 'low-density air.'

Engines gasp, propellers flail inefficiently,

and wings find scant support. To stay aloft in

this rarefied stuff, you must fly over the

ground faster than normal, though your airspeed

indicator, which is thrown out of calibration,

reads the same. For an anecdote, see Maritime Air.

|

DF Direction Finding, generally

referring to a primitive radio receiver and

instrument on the ground at an airport control

tower or a Flight

Service Station (FSS).

The

use of DF for assisting a lost pilot requires two-way

radio communications ("Which way,

Amelia?"). Typically, the operator on

the ground will say over the radio, "Give me a

short count, please." The pilot responds,

"1-2-3-4-5-4-3-2-1, over." The DF needle indicates

azimuth to the aircraft

which can be transmitted by voice to the pilot (as

soon as he or she remembers to release the

microphone key).

You are

invited to admire a world-class collection of

radio direction finders here.

ADF, Automatic Direction Finding is

an onboard receiving instrument, with a needle

that continuously indicates bearing

to a selected radio beacon

on the ground or commercial broadcast

station. The instrument on the right has

been manually set using the knob so that the

aircraft's heading, 340 degrees, appears under the

lubber; meanwhile, the

needle, which automatically points to the tuned-in

radio station or beacon, is

indicating that the aircraft is indeed homing on that heading with

no apparent crosswind. ADF, Automatic Direction Finding is

an onboard receiving instrument, with a needle

that continuously indicates bearing

to a selected radio beacon

on the ground or commercial broadcast

station. The instrument on the right has

been manually set using the knob so that the

aircraft's heading, 340 degrees, appears under the

lubber; meanwhile, the

needle, which automatically points to the tuned-in

radio station or beacon, is

indicating that the aircraft is indeed homing on that heading with

no apparent crosswind.

| ADF

dates back to olden times, long before the

VOR became a reality in

aviation. Which explains what you hear

even today in radio broadcasts, "We pause

now for station identification [just in

case there's some lost soul in the sky

who's trying to use his or her ADF to

figure out where the hell he or she

is]."

Personal

Note The ADF on the panel in Two-Four Fox was

routinely kept tuned to KNX

1070 AM, a 50,000-watt 'clear channel'

broadcast station located near Torrance

Airport. The needle always pointed

home on flights

all over the West, even from as far away

as the tip of Baja

California.

|

DME Distance

Measuring Equipment, an instrument that determines

distance of the aircraft from a selectable

navigation aid on the ground.

The DME in the aircraft acts

like a transponder, only

in reverse, sending out a pulse of radio energy in

all directions and measuring the time interval for

the return signal at the speed of light from the DME

on the ground.

The facility on the ground is usually

co-located with a VOR and is

operated under a "frequency pairing

plan." The combination is called VORTAC, an acronymic

portmanteau, which combines VOR

with TAC, which is an abbreviated TLD

for TACAN, which stands for Tactical Air Command Air

Navigation. Clear?

DOF Degrees of

Freedom, of which every solid object enjoys six.

Here are their names in aviation parlance alongside

their corresponding (nautical terms in parentheses).

- Moving up and down

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ climbing/diving (heaving)

- Moving left and right

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ slipping/skidding

(swaying)

- Moving forward and backward

~~~~~ accelerating/decelerating (surging)

- Tilting forward and backward

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ pitching (pitching)

- Turning left and right

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ yawing (yawing)

- Tilting side to side

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ rolling (rolling).

drag Force acting to

retard the motion of the plane or to keep people

from having fun at a party.

All

things that move through fluids experience drag.

Airplanes are distinguished by the fact that for them,

there are two kinds of drag. Common old ordinary drag

is called 'parasite' drag, which becomes greater with

increasing speed, the same as for barracuda and boats,

bikes and blimps, bullets and buses. Airplanes

also experience a pernicious form of drag, which

paradoxically increases at low airspeeds. It is called

'induced' drag -- induced by the act of flying. All

things that move through fluids experience drag.

Airplanes are distinguished by the fact that for them,

there are two kinds of drag. Common old ordinary drag

is called 'parasite' drag, which becomes greater with

increasing speed, the same as for barracuda and boats,

bikes and blimps, bullets and buses. Airplanes

also experience a pernicious form of drag, which

paradoxically increases at low airspeeds. It is called

'induced' drag -- induced by the act of flying.

Added together and graphed against

airspeed, these two drags form a U-shaped curve.

Corresponding to the bottom of the curve is the

'minimum drag speed,' usually about 30% above the

airplane's stall speed. In

still air, this is the most efficient airspeed,

giving the greatest distance for the least fuel

consumption.

By the way, since drag is overcome by

thrust (or 'power'), an airplane exhibits a U-shaped

'power curve.' Hence the expression that has been so

rudely appropriated by management and politicians,

"getting behind the power curve." It means flying so

slow that no amount of power can prevent a stall.

drift meter Telescopic

instrument (obsolete) used in dead

reckoning, that enabled an aircraft navigator to

peer down through the aircraft's fuselage

and measure the lateral motion of objects on the

ground thereby enabling adjustments of the aircraft's

heading to correct for

crosswind. drift meter Telescopic

instrument (obsolete) used in dead

reckoning, that enabled an aircraft navigator to

peer down through the aircraft's fuselage

and measure the lateral motion of objects on the

ground thereby enabling adjustments of the aircraft's

heading to correct for

crosswind.

One obvious limitation:

clouds that obscure the ground. For flying

over open water, whitecaps can be tracked; however,

for that, a wind at the surface must be greater than

about 10 knots (see Which way,

Amelia?)

DUAT FAA's Direct User

Access Terminal, a free service for qualified pilots,

providing self-service weather briefing, flight

planning and filing.

E6B

Computer A circular slide-rule used to perform

in-flight calculations, such as time-distance-speed,

fuel consumption, and wind-triangle. E6B

Computer A circular slide-rule used to perform

in-flight calculations, such as time-distance-speed,

fuel consumption, and wind-triangle.

Doesn't have batteries.

That's neat. Not only that but, unlike GPS, the E6B is not disabled by

solar flares in the daytime.

elevator

The movable surface at the trailing edge of the

stabilizer (the horizontal part of the empennage).

Operated by pulling or pushing the control wheel (or

stick), the elevator controls pitch

(animation).

Many

planes have a single, movable surface ('stabilator').

| 'Elevator' is a misleading

term. Within limits, the throttle controls

'elevation.' The elevator -- through pitch

-- controls airspeed.

While it is true that

pulling back on the control wheel, which

pushes down on the tail, imparts an upward

motion to the plane, the long-term effect

is to slow your airspeed. Enough of that

and you achieve a stall.

Old saying: "To go up, pull back. To go

down, pull all the way back."

|

ELT Emergency Locator

Transmitter, a radio beacon mounted in the aircraft

usually near the tail, activated by an accelerometer

in the event of a crash. The signal is picked

up by low-earth orbiting satellites for use in search

and

rescue operations.

empennage The tail assembly of an airplane,

including rudder and elevator.

Empennage is one of the few pure

aviation terms and was derived from the French word

(tail feathers of an arrow). Other French

contributions: aileron, fuselage, and longeron.

engine, critical

The most important flight parameter in multi-engine

flying is Vmc, which represents the expression

"minimum controllable airspeed with the most critical

engine out."

The most critical engine for

a twin is the one on the left wing, which is

determined by the P-factor.

For a single-engine aircraft, the most critical

engine is... never

mind.

engine, General

Aviation The most

common powerplant for light aircraft may be

described as [deep breath here]...

...internal

combustion engine, gasoline-powered,

spark-ignition, with four-stroke

reciprocating-pistons, dual-magnetos,

normally-aspirated carburetor or servo-managed

fuel injection, with or without turbocharging,

configured with either four or six

horizontally-opposed cylinders, displacing 100 to

400 cubic inches of swept volume, air cooled or

(rarely) liquid cooled, with inlets and exhausts

managed by overhead poppet valves engaged by

spring-return rocker arms activated by externally

sleaved push-rods riding on gear-driven cams in

the crank case, producing 100 to 300

brake-horsepower at sea-level, either directly

driving or via reduction gear to spin a metal

propeller with two- or three-blades, delivering

thrust by fixed-pitch or by pilot-selectable,

governor-controlled, constant-speed between 1,500

and 2,800 RPM.

The

two most prominent manufacturers are Teledyne

Continental

Motors and Textron

Lycoming, with BRP Rotax

taking a strong position in the LSA

market.

You can tell

quite a lot about an airplane's powerplant by

its model number, for example the Continental GTSIO-520C

features...

Geared

propeller, Turbo-Supercharged,

direct fuel Injection,

horizontally Opposed, 520Cubic

Inches; for number of cylinders, you have to

know that, for the same displacement,

Continental favors six and Lycoming four.

envelope, flight A representation of

limits that characterize the performance of an

aircraft in varions operating modes, as exemplified

for a light aircraft in level, non-maneuvering flight

in the diagram on the right. Observe...

- Stall Speed sets the

lower boundary on airspeed at all altitudes

dominated by induced drag and

is seen to increase with altitude: This edge of

the envelope mandates that one must move faster

through the air the higher one flies to keep the

plane from stalling.

- Drag Limit sets the upper

boundary on airspeed at lower altitudes dominated

by parasite drag and is seen

to increase with altitude, as the rarified air

reduces its resistance to flight, allowing the

plane to fly higher and faster until the...

- Engine Limit sets the

upper boundary on airspeed at higher altitudes

dominated by the volumetric efficiency of the

engine in developing power for thrust,

decreasing with altitude and thus slowing the

plane until reaching...

- Maximum Altitude (Service

Ceiling) at which the Engine Limit

boundary intersects the Stall Speed

boundary at the top of the...

- Level, Non-Maneuvering Flight

Envelope, such that an aircraft flying

anywhere within the green

area can fly at a constant altitude

with extra power available for climbing to a

higher altitude, increasing airspeed, maneuvering

in turns, and overcoming turbulence.

- Maximum Speed for level

flight is seen to be defined at the intersection

of the Engine Limit and the Drag Limit.

- Minimum Drag is

characterized by induced drag and parasite drag

being approximately equal, which occurs typically

at 1.3 times stall speed, and is seen to determine

the

- Maximum Distance the

flight can achieve in the absence of headwind.

Unlike weight-and-balance,

which imposes boundaries that must never be crossed,

flight outside the envelope depicted here may be

safely accomplished by maneuvers from inside the green area. Zooming, for example, is a

transient maneuver which trades airspeed for

altitude. Within redline

limits, diving trades altitude for airspeed and can

be sustained so long as there is plenty of altitude

AGL to spare. See "pushing the envelope."

ETA Estimated Time of

Arrival at a fix or destination (preferably GMT). Distinguished from ATA, Actual Time of

Arrival.

ETE Estimated Time

Enroute to next fix (usually in minutes) or to

destination (hours and minutes), critical for

estimating fuel requirements. Distinguished from ATE, Actual Time

Enroute.

FAA Federal Aviation

Administration, U.S. Government institution

responsible for regulating

all aspects of aviation.

FADEC Full Authority

Digital Engine Control.

Just the thing for 21st

century flying, especially in light aircraft with

diesel engines that burn jet fuel. FADECs

monitor and simplify engine operation (throttle,

propeller, mixture), enable single lever power

control, support improved engine starting , reduce

fuel consumption through parameter optimization, and

perform real-time data logging.

fail-safe Does not mean

the same as fail-proof. Everything made

by man fails (same for all other things, come to think

of it).

| A fail-safe system

incorporates redundancy ('back-up'), so that

an isolated failure

(‘single-point-of-failure’) shall not result

in catastrophe. Moreover, a

single-point-of-failure must not go

undetected (‘unrevealed’ is my term for

it). That would obviate

redundancy.

The popular juxtaposition

‘safety-and-reliability’ has meaning only

by virtue of systematic measures that

assure the joint unlikelihood of simultaneous

multiple failures.

Piston engines have dual

ignition systems, both independent of the

plane's electrical system, with two spark

plugs in each cylinder energized by

separate magnetos that are individually

tested before take-off. Planes also

have two wings; however,...never mind.

|

FARs Federal Aviation

Regulations ("regs").

FBO

Fixed Base Operator, an airport concessionaire

(sometimes also the airport owner) who offers vital

services, including fuel, repair, and ground

transportation.

Some FBOs run charter services and

sell or rent airplanes. The etymology of FBO is

unknown to this author. I like to suppose that it

was originally a term of distinction: the early

'barnstormers,' always on the move, would not have

qualified for any term with 'fixed' in it. {Egg

Plant

on Wheels}

FBW Fly-By-Wire, flight

controlled from the cockpit by

electronic signals in place of direct mechanical

connections to stick and rudder pedals via cables and

hydraulic lines, augmented by computer

processing of sensor information to fulfill

pilot commands efficiently and safely.

FIKI Flight into

known icing. Not recommended -- forbidden,

actually -- except for aircraft equipped with

de-icing features and a pilot who knows how to use

them.

final,

(final approach)

See pattern.

fix Location in space

at a particular time reckoned by the pilot or

determined automatically (see GPS,

LORAN) during flight.

The term 'position' (the P

in GPS) is most frequently used to describe a

flight's location with respect to a feature on the

ground. The word 'waypoint' refers to a

'position' along a planned course.

flap Surface on the

in-board trailing edge of each wing, which when

extended deepens the effective thickness ('camber') of

the wing, changing the relationship between lift and drag.

Strictly speaking, flaps do not

increase lift, which in steady flight equals the

weight of the aircraft. With the flaps extended,

stall speed is lessened, permitting slower flight

for landing. (Cowl flaps are a different thing; they

control the cooling of the engine. Marital flaps are

cockpit discussions resulting from both partners

holding pilots' licenses.)

flare Increasing pitch,

nose up, just prior to landing, a rounding-out

maneuver intended to transition from descent on the

glide path to horizontal motion -- on the runway, of

course...

There are three simple

rules for making a smooth landing.

Unfortunately no one knows what they are.

-- Old Aviation

Saying

| Sitting in the right seat of

a Skylane, I watched with admiration while

the pilot executed a perfect approach in a

stiff but steady wind at Flagstaff, Arizona,

flaring just right so that, with the plane

nearly stopped, the wheels might 'smooch'

the pavement without even squealing --

except for one thing: I could see the shadow

of the right main gear wheel on the runway

four feet below the right main gear

wheel. The pilot peered over the instrument

panel and grinned, preparing to taxi off the

runway and accept my applause. Then all at

once: ka-thunk. Glad I was there. |

flight level (FL)

Assignment by ATC

for IFR altitude separation of

flights above transition

altitude of 18,000 feet MSL,

which is safely higher (AGL) than

highest terrain in the U.S.

FL is given in multiples of 500

feet using standard sea-level atmospheric pressure

of 29.92 inches of mercury. History of the

concept provided by Altitude Telemetry.

flight log A document

created before

take-off and updated by the pilot while aloft to

keep track of information essential for the safe

execution of the flight. Here is an example of a

modern flight planning form,

specifically designed to fit on a knee

board.

| Conventional abbreviations

are abundant, including ALT altitude (MSL), ATA actual time of

arrival, ATE actual time enroute, Dev

(magnetic) deviation, ETA

estimated time of arrival, ETE

estimated time enroute, LEG leg (distance or

fuel consumed between waypoints), MH

magnetic heading, REM (distance or fuel)

remaining, TC true course, TH true heading,

Var (magnetic) variation, WCA wind

correction angle. |

flight, perfect That

perfect flight repays the requisite diligence

deserves an artful treatment.

flight plan

A document prepared by the pilot and submitted to Flight Service (in person, by

phone, or by radio).

| Under VFR,

filing a flight plan is optional. The pilot

'opens' the flight plan shortly after

take-off and 'closes' it just prior to

landing (or by telephone after landing). An

overdue flight triggers search-and-rescue

operations along the flight plan route.

Under IFR, a flight plan

is required and forms the basis of a clearance. |

Flight Service

Part of the services offered to all pilots by the

FAA. Briefers at hundreds of locations reply to

pilot requests for weather information --

information, not advice -- by telephone and radio.

They operate a network over which flight planning

information is communicated. Also see DUAT.

I'd rather be down

here wishing I were up there than up there

wishing I were down here.

-- Old Aviation

Saying

flying, real What birds and

light airplanes do (see Doggerel

in

the Sky).

FMS Flight Management System, subset

of glass cockpit,

flat-screen depicting an ensemble of flight and

navigation instruments plus other panel gauges.

FOD Foreign Object Damage,

can result in a "turbine stall" as the air flow is

disturbed by the ingestion of snow, sludge or, ugh,

a bird in a jet engine.

As with a stall,

the remedy in your owner's manual may be

counter-intuitive: Immediately pull back on

the thrust lever for the affected engine. FOD

will become increasingly relevant with the growth of

the VLJ fleet.

fugoid See phugoid.

fuselage The central body portion of an

aircraft designed to accommodate the crew and the

passengers or cargo.

Fuselage is one of the few pure

aviation terms and was derived from the French word

(spindle-shaped). Other French contributions: aileron, empennage,

and longeron.

gate, approach Imaginary

point in space that marks the beginning of the common

path to a given runway, most

commonly on an ILS approach.

The term was appropriated by

air traffic control in the 1950s from railroad

parlance, wherein gates are marked by wayside

signals to protect trains from one another in

approach to an "interlockings" (yes, with an

's'). See "Rails

in the Sky."

GCA

Ground Control Approach. The GCA has two

high-resolution radars that track the plane inbound,

one for the approach course, the other for the

glide-slope.

The requisite airborne equipment is

nil. All you need is a two-way radio. Thus, GCA can

be considered a last resort for getting one's

backside on the ground when everything airborne has

run amuck.

The special GCA radar facilities

are rare -- most have been de-commissioned. Unless

there's an emergency, you have to make an

appointment to get some practice.

GCT Greenwich (England) Civil Time,

historic predicessor to GMT.

| At the time of Amelia

Earhart's last flight in 1937, worldwide

agreement had not yet been reached for

referencing time zones to a common

meridian. Indeed, the radiomen aboard

USCGC

Itaca, the picket ship loitering hard

by Howland

Island awaiting the arrival of the

flight, were using a local time zone

displaced on a half-hour from GCT

(+11:30)! The primitive radio

protocols of the 1930s with their staggered

transmitting and receiving times

("transmitting quarter past the hour,

listening quarter to the hour") resulted in

blocked two-way communications, with tragic

consequences. |

General Aviation

What's left over when you subtract out military and

airline operations. You have your corporate jets,

your crop-dusters, and -- well, please don't ask,

"Oh, you mean like Piper Cubs?"

The Piper Cub is the

safest airplane in the world; it can just barely

kill you.

--

Max Stanley, Northrop test pilot

Along with Beech and other

companies, Piper manufactures many fine General

Aviation aircraft today -- always with their wings

on the bottom, by the way. Piper

Cubs are history. The most popular

private planes are made by Cessna, and like the

venerable Cubs, they have their wings (and petrol

tanks) on the top, which means no fuel pumps to

fail, no interferences with spectacular views out

the windows for passengers, and no ungraceful

entries for ladies in miniskirts.

All low-wing birds

must be extinct.

-- Old Cessna

Pilot

Private flying is a scarce privilege,

almost uniquely American. Nobody, though -- not even

an aviation enthusiast -- would say that private

flying is the most pleasurable activity in the

world. That terminology, by convention, is reserved

for something else. For many persons, a trip in the

sky aboard a light airplane ranks as a close second.

Not everybody agrees.

GMT Greenwich Mean Time, also

called 'Zulu.' Noon in November in New York is

'one-seven-zero-zero Zulu.' Being gradually

displaced by CUT

(Coordinated Universal Time).

GPS Global

Positioning System, precise, feature-rich navigation

system using signals received from a fleet of

low-orbiting satellites. Also see FMS.

ground effect

Increased pressure underneath the wings produced by

flying close to the ground. An overloaded airplane

taking off on a hot humid day may not be able to fly

without it. Upon reaching the airport boundary, such

a hapless airplane can experience another kind of

ground effect.

groundspeed

The speed (in knots usually) at which the airplane

moves ('makes good') over the ground. Distinguished

from airspeed. With a

'tailwind,' the groundspeed is faster than the

airspeed. With a 'headwind,' the groundspeed is,

alas, slower.

GUMP Abbreviated

pre-landing checklist: Gas (fuel selector on the

fullest tank), Undercarriage (that's "landing gear,

Old Chap"), Mixture (full rich), Propeller (highest

RPM).

| On an instrument

approach, the pilot has plenty of

things to do. The author concocted

"Check freak killers and Miss High Time's

Speed" for pre-landing checklist: set up

approach frequency (freak); study approach

chart for obstacles and terrain hazards

(killers), recite the missed approach

procedure (miss), review decision altitude

(high), set timer for missed approach limit

(time), and slow to approach speed (speed).

After all that, GUMP. |

glide Un-powered

descent (see throttle).

For a typical light plane, gliding at

65 knots, the descent rate is 600 feet per minute

(about 6 knots in the downward

direction).

gyro A

spinning mass inside certain instruments vital to the

safe conduct of flight under IMC.

There are three such instruments.

The 'artificial horizon' or 'attitude

indicator' is the primary gyro instrument. Because

of the idiosyncratic behavior of the magnetic

compass, the pilot relies instead on the 'direction

gyro' or 'heading indicator.'

Finally, there's the old 'needle-and-ball' or the

new 'turn coordinator' that tells the pilot the rate

at which the plane is turning and whether the turn

is 'coordinated' (yaw in balance

with roll).

hangar An enclosure for

housing aircraft. From Medieval Latin angarium,

shed for shoeing horses.

heading

The direction the plane is pointed with respect to

True North (true heading) or Magnetic North

(magnetic heading). Because of wind, heading

does not necessarily correspond to the intended course, the latter achieved by

a 'cross-track correction' (see crab). heading

The direction the plane is pointed with respect to

True North (true heading) or Magnetic North

(magnetic heading). Because of wind, heading

does not necessarily correspond to the intended course, the latter achieved by

a 'cross-track correction' (see crab).

headway Separation,

measured either in nautical miles or time between

successive aircraft flying in the same direction on

a common airway at the same altitude.

Headway has made its way

from nautical terminology to aviation via

railroading (see approach gate). Leeway is another

transportation concept that ought to be

brought into aviation (see "Headway vs Leeway").

HIRL High-Intensity

Runway Lights, a row of lights located at the approach

to a runway that flash in rapid succession to provide

a visual reference at the conclusion of an ILS approach.

For the story of its

invention, see "Flash

in

the Sky."

holding pattern

In planes -- unlike trains and automobiles -- one

cannot just tell the vehicle to stop when there is

congestion ahead. The holding pattern was invented to

cover that case. It is part of the concept of a

'clearance limit' under IFR.

| The holding pattern is

shaped like a race track in the sky.

Actually a stack of them, each separated by

a thousand feet. One plane at a time can

occupy any particular level. Think of a half

dozen Indianapolis 500's piled up over a

navigational fix.

The holding pattern

comprises four parts, each requiring one

minute. (1) Upon reaching the

assigned fix, you make a 180-degree turn

at three degrees per second; (2) fly

outbound for one minute on an assigned

heading; (3) make a 180-degree turn back

inbound at three degrees per second; (4) "home in" on the fix,

like cruising along the straight-away at

Indianapolis.

|

hood A large plastic

hat-like contraption with a drooping brim that

blocks the pilot's view out the window, thereby

simulating instrument meteorological conditions (IMC)..

The IFR instructor

acts as a safety pilot to watch for other airplanes.

The weather might be perfectly clear, but the

student 'under the hood' must conduct the whole

flight by reference only to instruments. {Under

the

Hood}

homing Steering toward

a waypoint or destination, often guided by ADF tuned to a navigational signal

such as a beacon.

As the aircraft approaches

the homing source, navigation errors decrease,

reaching zero overhead the beacon. For any

outbound course, of course, navigation errors

increase with distance, much the same as for dead reckoning.

The phrase honing

in

on may be an imperfect appropriation for

popular usage.

IFR Instrument

Flight Rules, a rigorous set of principles and

procedures that assure safe operation into and out of

airports and enroute separation from other aircraft,

in weather conditions that preclude operating under VFR, Visual Flight Rules.

One requirement is called a 'clearance,' which

constitutes a contract between the pilot and flight

controllers that sets forth the de-fault procedures

to be followed if a break-down occurs in

air-to-ground communications.

The informal expressions "flying on

instruments" or "flying IFR" mean controlling the

plane by reference only to gauges on the panel,

especially those that incorporate gyros,

a mode of flight necessitated by "IFR conditions,"

which is a phrase now generally replaced by "IMC" for "Instrument

Meteorogical Conditions."

ILS Instrument

Landing System, electronic equipment that guides an

airplane precisely onto the runway.

Two of its subsystems, 'localizer' and

'glide slope,' are radio transmitters on the ground

which define respectively the straight-in course

over the ground and the vertically slanting path to

the touch-down point. A pair of needles on the panel

provide the requisite guidance. On my approaches, it

looks like a sword fight.

ILS Approach,

a sequence of essential tasks performed by the pilot

in transitioning from cruising flight through to

touchdown using the ILS, typically

including at least 18 steps.

- Fly level at initial

approach speed on an assigned heading.

- Intercept the

localizer (vertical needle).

- Turn to

localizer/runway heading.

- Become "established"

on the localizer, correcting for

crosswind.

- Recognize "outer

marker" beacon, report to control tower.

- Deploy landing gear

and extend partial flaps.

- Intercept the

glide-slope (horizontal needle).

- Reduce power to final

approach speed

- Become "established"

on the appropriate descent-angle.

- Recognize "middle

marker" beacon.

- Extend full flaps and

maintain glide-path

- Descend to "minimum descent

altitude."

- Apply power and

maintain altitude if the runway is not

in sight.

- Recognize runway

approach lights,

- Report to control

tower "Landing assured."

- Reduce power, kick out

crab-angle, flare-out, and touchdown.

- Retract flaps, apply

brakes.

- Speed permitting, turn

onto assigned taxiway.

|

IMC Instrument

Meteorlogical Conditions (see IFR).

iniquity Flying under

the influence, with passengers. Compare to stupidity.

intersection A fix or

waypoint defined by the crossing of radials from two

omni stations.

A number of years ago, the FAA changed

all intersection names to five-letter words,

ostensibly pronounceable. Computers again, folks.

Back when I started flying, there were no such

constraints. Intersections were named for what

underlay them, usually a city. Thus, Anaheim became

AHEIM; Tustin, TUSTI; El Monte, ELMOO. Out in the

ocean, we had Albacore, which became ALBAS, and

Mermaid, which is now, alas, MERMA.

| My flying instructor John,

who is featured in several chapters (Two-Four Fox, License to Learn)

for his nonchalance about regulations,

did not himself have an instrument

rating. That did not stop him from

filing a “pop-up” IFR

request during one of my early

lessons. It was a night flight in

“actual” IMC. John and

I got vectored all over the Los Angeles

Basin.

“Two-Four Fox, report

Alhambra intersection," said the voice

on the speaker.

I was struggling with

altitudes and headings, but I watched

while John flicked his flashlight all

around the LA Sectional in his

lap.

“Here it is,” he said,

“La Habra is 15 miles further.”

“Um, John, you mean

‘farther’.”

“That’s what I

said. Hold whatcha got for another

15 miles.”

“For distances, the word

is ‘farther’

not ‘further’,”

said

I, pulling his chain. La Habra is

15 miles farther than

Alhambra.”

John dismissed my

pedantry with a shrug.

“Besides, John, didn’t

that guy tell us to report at the

‘Alhambra’ intersection not ‘La Habra’?”

He shined his flashlight

on the chart and handed me the mike.

“Yeah, guess you better tell ‘im we’re

there.”

|

Being limited by computer protocols

to five letters might not always be much of a

hindrance after all (ALHAM vs LAHAB)

knot Nautical mile per hour (MPH): 100 knots

corresponds to 115 MPH.

leeway Nautical

terminology, which, alongside headway,

has meaning in making the distinction between, say,

the flexibility of General

Aviation and scheduled airline operations.

lift The upward

force of the air upon the wings.

In level flight, lift acts vertically

(opposing weight) and produces -- well, level

flight. When you bank the

plane, part of the lift acts horizontally to cause a

turn.

"line-up and

wait" A clearance given by the Local Controller that

authorizes a plane ready for departure to move onto

the runway in preparation for "cleared for takeoff"

(changed in 2010 from "taxi into position and hold").

Local Controller The

person in the Control Tower who authorizes takeoffs

and landings.

longeron A

fore-and-aft framing member in an airplane.

Longeron is one of the few pure

aviation terms and was derived from the French word

(to pass along). Other French contributions: aileron, empennage,

and fuselage.

LORAN Long Range

Navigation system applies an onboard receiver to

process signals from a set of ground-based,

low-frequency transmitters, generally replaced now by

GPS.

LSA Light Sport

Aircraft [Work in Process]

mayday

internationally recognized distress signal via

radiotelephone (from the French m'aider),

shortening of venez m'aider "come help me!"

MFD Multifunction

Display, a member of the expanding family of

flat-screen, glass cockpit instruments.

mile

Two sizes: statute mile (sm

5,280 feet) and nautical mile (nm 6,080 feet),

resulting in two different units for airspeed and winds aloft.

You can get from one to the

other by multiplying or dividing by 1.1515, but

there's seldom enough time for that. The nautical

mile corresponds to one minute of latitude.

Since the 1960s only nautical miles

are used in aviation, which, like GMT,

was a long-overdue standardization for safety (see

Which Way,

Amelia?).

MSL (Above) Mean Sea

Level, the measurement of altitude provided by the

airplane's altimeter.

Compare to AGL, Above Ground

Level. Also see flight

level. MSL (Above) Mean Sea

Level, the measurement of altitude provided by the

airplane's altimeter.

Compare to AGL, Above Ground

Level. Also see flight

level.

Illustrated on the right is

the altimeter indication for a plane at 6,264 feet

MSL.

navigation Determining

one's location and guiding the control of heading to

achieve a desired course.

Appropriated by aviation

from nautical parlance, the term is gradually being

replaced by avigation.

Navigator's

Definitions: 'Latitude' is where we are lost,

and 'Longitude' is how long we have been lost

there.

-- USAF Navi-guesser - Woo Hoo

NDB Non-directional beacon.

needle-and-ball

Obsolete predecessor to the turn-coordinator. needle-and-ball

Obsolete predecessor to the turn-coordinator.

NOTAM NOtice To AirMen.

Never mind the

gender-specificity, NOTAMs are official bulletins

distributed from the FAA by

subscription and via up-to-the-minute communications

over the radio from Flight

Service, obligatory information generally for

the safety of flight.

north Direction toward

the North Pole (true north) or toward a site located

in Eastern Canada (magnetic north), a reference used

to determine an aircraft's heading as measured by a compass.

numbers, phonetic

Officially, there are only twelve ('one-two')

numbers used in radio communications: Zero, One,

Two, Three (pronounced tree), Four (fow-er), Five

(fife), Six, Seven, Eight, Niner, Hundred, Thousand

(tou-send).

| An altitude of 12,500 feet

is said "One-two tousand, fife hundred." You

do hear pilots taking shortcuts ("twelve

point five") but never controllers. By the

way 'point' is supposed to be said

"day-see-mal."

The numbers ten, eleven,

and twelve appear only preceding o'clock

to designate the relative bearing of traffic

or landmarks. 'Twelve o'clock' means

straight ahead, 'eleven o'clock' means 30

degrees to the left of straight ahead,

'one o'clock' means 30 degrees to the

right, and so forth. Pity pilots who have

grown up with digital watches.

In the expression, "inbound

with your numbers," the term is used to

summarize the current operating conditions

and procedures at an airport to save

repeated instructions from the controllers

(see ATIS).

"Landing on the numbers"

means touching down on the painted

numerals -- hey, at the beginning

of the runway.

|

omni Short

for 'omnirange', the most common radio navigation

device in current use (also called VOR).

The term is used here for both the ground facilities

and the flight instrument. Unlike ADF,

reception of a VOR signal is limited to 'line of

sight' from the station to the aircraft. omni Short

for 'omnirange', the most common radio navigation

device in current use (also called VOR).

The term is used here for both the ground facilities

and the flight instrument. Unlike ADF,

reception of a VOR signal is limited to 'line of

sight' from the station to the aircraft.

There are hundreds of omni-range

stations in the United States and elsewhere. Each

defines a set of 360 invisible 'radials,' each

resembling the spokes of a wheel and corresponding

to the magnetic bearing of

the plane's position (not the airplane's heading). Certain radials are

shown on charts connected together forming the

'Victor' airway system.

The pilot first tunes his or her

omni receiver to the frequency of a nearby

station. Then, by centering a needle, the magnetic

course to or from the

station can be determined.

over Spoken at the end

of a radio transmission -- only when required to

inform the listener that a reply is expected.

Movie-makers take note: the term does not routinely

conclude every transmission.

pattern,

("landing pattern") A rectangular

flight path associated with each runway, one side of

which is the runway. It forms the conventional

framework for controlling the orderly flow of

aircraft to and from an airport.

There are five legs: upwind (straight

ahead immediately after take-off), crosswind (a ninety

degree turn at the departure end of the runway

either left or right depending on the published

pattern for that runway), downwind

(parallel and to the side of the runway), base (perpendicular

to the runway at the approach end), and final (lined up with

the runway, descending for touch-down).

Generally, you depart on a 45

degree angle from the upwind leg and enter the

pattern on a 45 degree angle to the downwind leg

("on the forty-five"). At controlled airports, you

may request such alternative procedures as a

"straight-out" departure or a "straight-in"

approach. And sometimes you will get cleared for a

mouthful: "mid-field crossing downwind entry."

Listen up.

| "Cutlass Three Seven

Romeo, Orange County Tower, continue on

the forty-five, for initial approach to

Runway One-Niner Right, remain west of the

airport, turn right abeam of the tower,

make mid-field crossing to a downwind

entry for Runway One-Niner Left and report

turning base."

"Yeah, I can do all

that. Thanks."

"I thought

so. You're welcome."

|

In Canada, by the way, MFCDE is the

standard procedure for pattern entry. It has

a significant advantage: altitude separation.

Since entry takes place directly above the runway,

any other aircraft in the pattern at that location

are rolling along the ground -- well below the

entering aircraft's pattern altitude (typically

800 to 1,000 feet AGL).

PFD Primary Flight

Display, a flat-screen glass

cockpit that combines FMS

and SVS.

P-factor A tendency

for a single-engine aircraft to yaw

to the left at high angle-of-attack,

most pronounced immediately following take-off and

during climb-out. In a twin, the P-factor

defines the 'critical engine'.

| As the wheels lift off the

ground at the beginning of your first flying

lesson, it will feel like your plane has hit

a patch of ice. Your instinct will be

to turn the "steering wheel" to the right;

however, that will only make matters worse

(see adverse yaw).

At that moment -- and often thereafter --

your instructor smirks and hollers over the

sound of the engine, "Get on that right rudder pedal!"

The propeller customarily

rotates clockwise as viewed from the rear.

Drag in "air

screw" might be expected to bank the

aircraft counterclockwise; however, the aelerons have much

greater mechanical advantage in the roll axis than the

propeller tips, making any banking effects

negligible. So why does the P-factor

show up in yaw?

Several explanations are

offered in aviation literature. One

suggests that the empennage

is rigged in the factory to match airflow

forces passing along the fuselage and

optimized for cruise speed. Those

forces are not exactly balanced in a

climbing maneuver. At full climb

power and with reductions in airspeed toward a stall, that effect

would decrease not increase. Another

explanation has it that the vertical stabilizer

gets pushed to the side by clockwise

spiraling propwash. However, that

would also decrease with speed, as more

time will be allowed for the spiraling

component of airflow to dissipate before

the rear of the plane can catch up to

it. Gyroscopic 'precession' of the

engine and propeller may contribute to the

P-factor, but that will manifest itself

only as a transient torque during pitch rotation not

as a steady-state condition while

climbing. Oh right, the gyroscopic

torque acts in the opposite direction to

the P-factor, yawing the aircraft to the

right not the left.

The best explanation is

based on the observation that in a climb

the upward inclination of the fuselage

tilts the plane-of- rotation of the

propeller away from its normal orientation

-- perpendicular to the flight path.

Accordingly, the downward-moving blade on

the righthand side of the aircraft is

advancing at an angle into the

relative wind and thus developing more thrust than the

upward-moving blade on the lefthand side,

which is retreating out of the

relative wind.

|

phugoid Often

spelled fugoid -- different

ancient roots for the same word, which means

"flight" in the sense of fleeing (think of

fugitive). The term is used in the phrase

"phugoid maneuver" to describe the oscillations,

most commonly in pitch, of an

aircraft that is allowed to fly on its own accord

(see diagram).

| A small atmospheric

disturbance, can cause a plane, which has

been trimmed for level

flight hands off, to pitch nose downward,

say. Airspeed increases, which

increases lift, raising the nose back up

again. With no corrections by the

pilot, inertia produces an overshoot into a

nose upward attitude. Airspeed now

slows, which decreases lift, lowering the

nose back down again. For a light

aircraft the period of oscillation might be

as long as 30 seconds. |

Pilot-in-Command (PIC) has ultimate

authority over all aspects of flight.

In theory, the PIC can

decline to comply with clearances given by

Air Traffic Control (ATC).

Any assignment by ATC -- altitude,

heading, route, runway, speed -- can be

rejected by the PIC.

There is one

exception.

Hold

Short (of an active runway) may be the

only mandate in aviation -- the only

utterance by ATC -- that must be obeyed by

the PIC.

ATC and the PIC collaborate

to assure safety. Thus, as a

practical matter, the PIC will negotiate

with ATC to resolve clearance

issues -- in flight. On the ground,

though, ATC's "hold short" holds primacy.

|

pilotage Term

preferred by pilots in place of dead

reckoning.

pitch Rotation of an

aircraft about a horizontal axis perpendicular to

the direction of flight (nose-up / nose-down),

controlled by the elevator.

Pitch is also used to

describe the 'bite' of the propeller.

The propeller is just a

big fan in front of the plane used to keep the

pilot cool. When it stops, you can actually

watch the pilot start sweating.

-- Old

Aviation Saying

pitot tube

External pressure sensing device, an essential part of

the pitot-static system that serves the airspeed indicator plus altimeter and vertical

speed indicator.

Named for its inventor,

Henri Pitot (1695–1771) a French hydraulic engineer,

the pitot tube has an external opening on an arm

projecting into the windstream that registers

"stagnation pressure" (also called "ram pressure")

and a port on the side of the aircraft that

registers "static pressure." The difference

between these two pressures indicates

airspeed. The altimeter is an aneroid

barometer. It uses the static pressure, which

is not static of course but varies with

altitude. A third instrument, the "vertical

speed indicator," measures the rate of change in

static pressure.

The pitot-static

system is elegant in its simplicity, with no

moving parts. There are occasions, however,

when faulty airspeed

indications can result in tragedy (Colgan

3497 and AF

447). The pilot must be prepared to

reject indications that don't jibe with elementary

realities of flight...

| Landing a rented Cessna

172 at Warner

Springs in a strong crosswind from

the left, I set up a radical side-slip. With

left-wing down at some 30 degrees bank

angle, I throttled back. Thus,

though we would touch down on the left

side first, the plane's wheels were all

lined up with the runway and I was

grinning. Then I glanced down at the

airspeed indicator.

It was showing the plane to be flying at

under 20 knots! Note the exclamatory

punctuation. Meanwhile, the needle

on the vertical speed

indicator was pointing down at more

than 1,500 feet per minute!

Oh right, and the altimeter

was reporting that the plane had already

descended to an altitude below the

runway elevation!

After the landing I

reminded myself that, to save

manufacturing cost for the 172, the

Cessna people install only one

pitot-static port (a small hole) in the

fuselage -- on

the lefthand side. In a side-slip to the left, the

static port is picking up increased air

pressure, reducing its difference from

the ram-pressure and thus reducing the

indication of airspeed.

Also, the increased static pressure

tricks the instruments into [a] an

erroneously low altitude and [b] an

exceptionally high rate-of-descent.

More advanced designs (Two-Four Fox, for

example) have static ports on both sides

of the fuselage, which balance out the

effects of uncoordinated

maneuvers.

|

position (see fix).

position report Message

spoken by the pilot over the radio during

flight. Under IFR ,

position reports are mandatory, for they clear the

block of protected sky behind your flight for

another flight. Under VFR,

position reports are optional procedures for safety

-- to reduce the search area (ugh) following a

mishap in the sky (see anecdote in Taciturn).

The minimal format has a

venerable mnemonic PTAND for Position

Time Altitude ETA Next

(fix) & Destination. On July 2,

1937, Amelia Earhart might have given a position

report as follows:

| USS Ontario, Electra

NR16020, VFR from Lae, New Guinea, landing

Howland Island. Position abeam

Nukumanu Island, 0618 GCT eight thousand;

estimating overhead your location at 0955

GCT; estimating Howland 2022 GCT.

Sky clear above cumulus clouds; wind 090

degrees at 23 knots; making good 131

knots; standing by 6120 kilocycles. |

pushing the envelope The

expression began in aviation. With the presence

of VLJs in the aviation fleet,

private pilots may approach transonic regimes and will

encounter forbidden corners of the flight envelope.

| Every aircraft has