ating

back centuries in nautical history, the word 'headway'

was originally a contraction of the phrase 'ahead-way'

representing forward motion of a vessel, as

distinguished from 'lee-way', which referred to lateral

drift. In common usage, the word 'headway' has

come to mean "progress toward a goal," and 'leeway'

implies flexibility, freedom. In transit systems,

headway means the time between successive buses or

streetcars or trains. ating

back centuries in nautical history, the word 'headway'

was originally a contraction of the phrase 'ahead-way'

representing forward motion of a vessel, as

distinguished from 'lee-way', which referred to lateral

drift. In common usage, the word 'headway' has

come to mean "progress toward a goal," and 'leeway'

implies flexibility, freedom. In transit systems,

headway means the time between successive buses or

streetcars or trains.

Headway ranks alongside speed as a key

indicator of service performance. Policy-makers in public transit

systems have learned that ridership decreases

sharply when headways are made longer than about 15

minutes. The psychology is elementary.

Time spent standing around waiting to get on

is far more annoying than time spent in motion

waiting to get off (see the The

Grumble Factor). With

headways less than, say, 12 minutes, planning is

unnecessary; most patrons won't even bother to

consult the time-table.

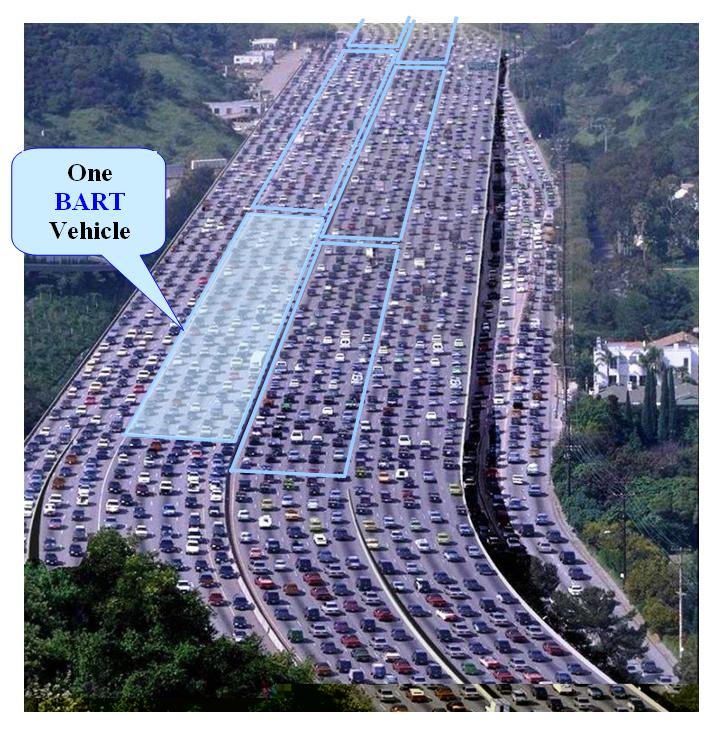

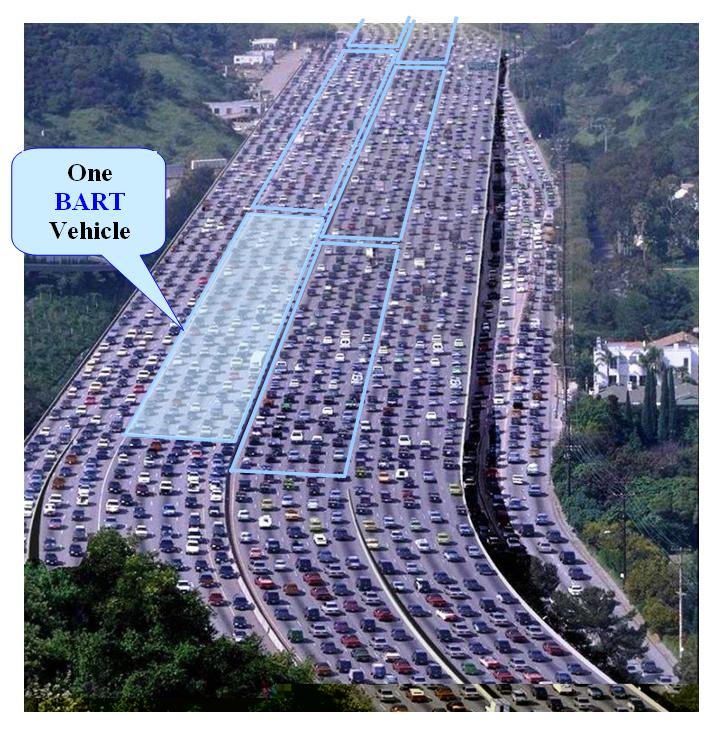

Nowadays, private

automobiles compete successfully with public

transportation in urban settings -- but by offering

flexibility ('leeway', so to speak) more than

speed. Congestion and parking see to

that. With transit headways longer than

30 minutes, patrons abandon public transportation

and take to the automobile -- hey in 'droves' -- this,

despite much higher cost for commuting by

car. For example...

| Back in

1960, a certain Inter-Mountain community

operated a successful city bus service on

15-minute headways. Ridership expanded

steadily to the point that there would be

standing-room-only for morning and evening

commuters. Traffic congestion and

problems with downtown parking did not

exist.

As a

"common good," public transportation

systems worldwide are subsidized. In

response to taxpayer complaints about the

amount of the subsidy, the city raised bus

fares. Ridership steadily expanded,

though, and so did suburbia. During

rush hours, all buses continued to operate

with "crush loads."

Someone

got the bright idea to reduce costs

by upgrading the fleet with bigger buses

and running them less frequently. It

worked. At 20-minute headways, the

city operated with 25% fewer buses and

drivers. Oh, but then, despite

explosive population growth, ridership

began to decline. People

bought cars.

Reduced

passenger loads allowed the city to

increase headways still further -- to 30

minutes -- while selling off buses and

laying off drivers. Ridership

plummeted. Soon there were two seats for

every passenger. By coincidence,

cars began clogging the streets and

downtown parking-lots filled up.

Finally,

at one-hour headways, the buses ran

virtually empty. A certain essayist

moved into the city in 1990 and took the

bus to work every day. Often as not,

he would be the only passenger on

board. He was puzzled about that.

One morning, his driver, an old-timer,

reprised the headway history.

|

pproaching the end of

the Petroleum

Age, economics will doubtless become more

significant in the choices people make for their

personal transportation. One might expect

public transportation systems in the U.S. to become

as popular as they were a hundred years ago --

indeed, as popular as they are today in many

countries. pproaching the end of

the Petroleum

Age, economics will doubtless become more

significant in the choices people make for their

personal transportation. One might expect

public transportation systems in the U.S. to become

as popular as they were a hundred years ago --

indeed, as popular as they are today in many

countries.

Private

automobiles will not be able to compete, despite all

of their 'leeway', so to speak. Congestion

will become merely an unpleasant memory.

Nevertheless, policy-makers in public transit

systems may have no choice but to make headways

longer and longer for petroleum-powered buses.

They won't run empty, though.

|