|

Copyright ©2011 by Paul Niquette. All rights reserved. |

|

What

sets the limit for the speed of a train? Curves,

mostly. Climbing

a grade, of course, speed will depend to some extent on

horsepower-to-weight

ratio. Coming down, it's curves again. On level

track, wind resistance

will play a role, as explored in the World's Fastest

Train puzzle. Tracks are seldom perfectly

straight for great

distances. There are hills and cities to steer

around and stations

to line up with. What

sets the limit for the speed of a train? Curves,

mostly. Climbing

a grade, of course, speed will depend to some extent on

horsepower-to-weight

ratio. Coming down, it's curves again. On level

track, wind resistance

will play a role, as explored in the World's Fastest

Train puzzle. Tracks are seldom perfectly

straight for great

distances. There are hills and cities to steer

around and stations

to line up with.

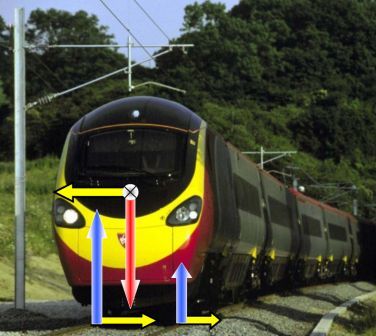

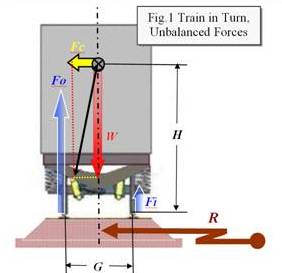

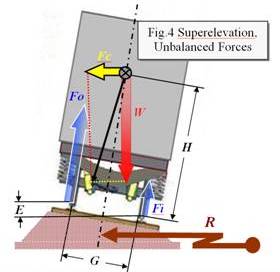

On the right we see a train negotiating a curve to the left. Superimposed are the unbalanced forces that tend to tip the train toward the outside of the curve, much as in the Circling: Ground and Sky puzzle.

Sharp curves are out of the question. For speed, radius of curvature R needs to be made as long as possible, but there are often limitations imposed by terrain or land-use commitments.

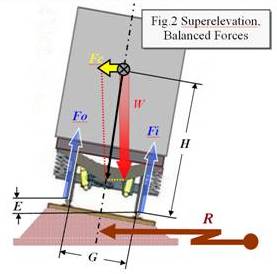

Figure 2 shows how superelevation, symbolized by E, can be used much like a banked highway to balance the rail forces (Fi = Fo ) thereby allowing trains to operate faster than might otherwise be possible along curvatures in the trackway. For given values of R and E, the two track forces can be balanced at only one particular train train speed, VBALANCED... Fc / W = E / G, and......where g = the acceleration of gravity (32.2 ft/sec/sec).

Every segment of trackway must be certified with what is called a 'civil limit', which specifies the maximum speed that a train can operate on it. In additon to the dimensions of curves as indicated here, civil limits must take into consideration all trackway conditions, including grades, switches, and station platforms.

Of course, trackways are never designed to change abruptly from straight to curved and back again. Instead, the rails are given a 'spiral' shape, gradually changing radius of curvature, between infinitely long, for straight trackway, to a fixed radius R, for a circular segment in the 'alignment'. Along the spiral, superelevation changes linearly from zero to its value E as indicated in Figure 4.

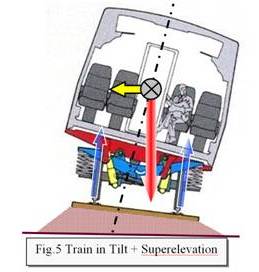

The tilting train was invented to overcome discomfort for passengers, the first being put into service in 1938. Figure 5 is a sketch of a high-speed passenger car traveling in a curve and tilted by a mechanical device atop the bogie. The tilt angle has been adjusted on the fly so that the passenger apparently experiences no lateral forces. Complete balance might seem to be ideal. It is not.

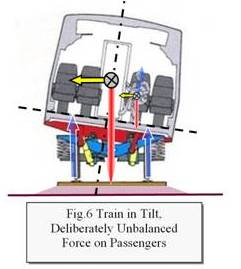

Figure 6 shows the preferred application. An accelerometer fitted in the first bogie of the train measures lateral forces as the train enters a curve. The signal is processed by computer and sent down the trainline. Computer-controlled hydraulic rams tilt each coach into the curve, up to a maximum inclination of 6.5º. The tilting system compensates for no more than 75% of the lateral force of a curve and is only employed at speeds above 44 mph. Incidents of tilt-train 'sea-sickness' are rare, as 25% of lateral forces are still felt by the passengers.

Cruise Speed ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ VCRUISE = 200 mph

|

|

Figure

1 is a sketch of a train-car traveling along a curve

of radius R

on a track with

Figure

1 is a sketch of a train-car traveling along a curve

of radius R

on a track with

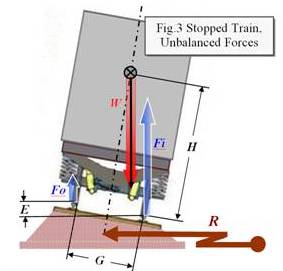

Figure

3 is included here to address another limit, this time

on the values of

superelevation E in view of gravity's

tendency to tip a stopped

train toward the inside of the curve. The effect

is worsened by the

draw-forces between vehicles as the train starts

up.

Figure

3 is included here to address another limit, this time

on the values of

superelevation E in view of gravity's

tendency to tip a stopped

train toward the inside of the curve. The effect

is worsened by the

draw-forces between vehicles as the train starts

up.

Superelevations

are generally specified for an intentional 'unbalance'

of forces as shown

in Figure 4. Thus, at speeds approaching civil

limits, the train

will tend to be tilted outward from the center of

curvature.

Superelevations

are generally specified for an intentional 'unbalance'

of forces as shown

in Figure 4. Thus, at speeds approaching civil

limits, the train

will tend to be tilted outward from the center of

curvature.

Meanwhile,

objects inside the train -- in particular passengers

-- will be acted upon

by invisible, gradually changing forces from the left

or the right every

time the train enters a curve from straight, tangent

track.

Meanwhile,

objects inside the train -- in particular passengers

-- will be acted upon

by invisible, gradually changing forces from the left

or the right every

time the train enters a curve from straight, tangent

track.

According

to an article published by the

According

to an article published by the