|

Copyright ©2011 by Paul Niquette. All rights reserved. |

|||

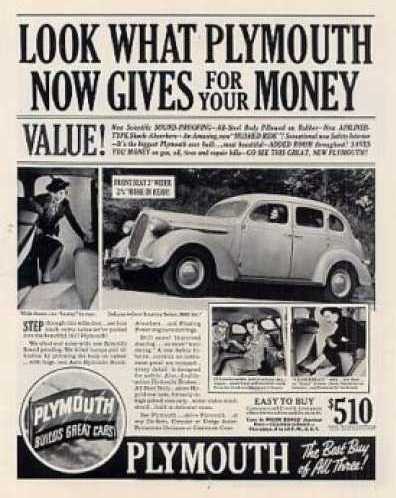

The headline in this 1937 advertisement was prophetic.

A life-changing event took place at about that time: The guy was hired by Dan Gerlough as "research assistant" and given his own laboratory at the Institute for Transportation and Traffic Engineering (ITTE), then occupying war-surplus barracks on campus. He was put in charge of instrumentation for Landmark Studies, including Automobile Crash Injury Research. Cited in Ralph Nader's 1965 polemic, Unsafe at Any Speed, UCLA conducted the world's earliest crash tests using real automobiles and anthropometric dummies, differing sharply from contemporaneous research at Cornell, which simulated automobile crashes using spring-loaded, two-dimensional plywood mockups on rails.The ITTE research team appropriated the expression second impact to address the reality that after a car comes to a crashing halt, the passengers inside are still moving, thence to be injured as they smash themselves against hardware features built into the car. The experimental objective, as summarized in Engineered Automobile Crashes, was to ascertain the efficacy of various restraining devices (lap belt, shoulder harness, chest-level strap) in preventing injuries to passengers resulting from frontal collisions. Solvers of the Historic Car Crash puzzle will find second impact to be a relevant subject. Full Disclosure: The 1937 Plymouth was not exactly donated to ITTE. The research assistant found an identical car in an Inglewood junkyard. Both cars were purchased for the same price with funds taken from ITTE's "instrumentation budget."  Instrumentation

was dominated by accelerometers, which were analog

devices, of course, and by high-speed motion picture

photography, the latter being shot at up to 2,400 frames

per second (25 ms per frame). A 100-ft roll of 16 mm

film went zinging through the camera in under two

seconds, recording more than 4,000 images. Instrumentation

was dominated by accelerometers, which were analog

devices, of course, and by high-speed motion picture

photography, the latter being shot at up to 2,400 frames

per second (25 ms per frame). A 100-ft roll of 16 mm

film went zinging through the camera in under two

seconds, recording more than 4,000 images.

The reel from the first crash test was quite entertaining when projected as a slow-motion movie of the anthropometric dummies thrashing about. The film was successful in identifying key events throughout the crash, but the individual images suffered from low resolution and were therefore unsuitable for publication in print."In a crash test," opined the research assistant, "there must be a precise instant at which a picture will best characterize the outcome." That instant, he thought, ought to be captured in a still photograph. And ITTE's research assistant had access to the ideal instrument for doing so, a Speed Graphic camera belonging to his father. The key question from back in 1954 is reprised here for the Historic Car Crash puzzle...

Both crash tests were conducted at 28 mph, and, based on images in the high-speed motion picture film from the first crash test, ITTE's research assistant made two observations...

Observation #2 That the rear-end of the car appears to be elevated on impact by 3.0 ft.

|