More or Less

To most people, progress always means "more."

Quite a few worthwhile developments, though, have resulted in "less."

There was once a marvelous invention called

the "horseless" carriage.

Then came the "wire-less" telegraph. And now

the "cordless" telephone.

Credit cards foreshadow the "cash-less" society;

electronic funds transfer systems, the "check-less."

Much progress attended the arrival of "water-less"

printing -- better known by its Greekish name, "xerography." (The law of

unintended consequences has prevailed. Thus, nearly submerged in a paper

deluge, we turn to ubiquitous personal computers electronically networked

together. The office of the future might indeed be "paper-less.")

The "feather-less" chicken didn't work out

very well, but the "seed-less" grape did.

Some say the "bark-less" dog and the "smoke-less"

cigar wouldn't be bad ideas for their neighbors and spouses, respectively.

So, why not the "motor-less" cycle?

Future

In varying degrees, all persons are futurists.

The future is illuminated only by opinion.

There are no facts about the future.

Debate is the ineluctable activity of the futurist.

An analogy serves no purpose in speculative

controversy except to illustrate an agreed-upon point.

Think seriously about principles. Make your

assumptions explicit. Invent a future. Then find a debating partner.

Be suspicious of all utterances that start

out in the first person singular. The least reliable source of the common

experience is oneself.

You want the common experience? Watch daytime

television.

An average is just one measure of "central

tendency."

You can drown in a lake the average depth of

which is one foot.

Watch those "bimodal distributions." The average

American has one breast and one testicle.

People often see in the future what they think

ought to happen, not what they think will happen. It is easy to contaminate

prediction with advocation.

Surprise-free projections can turn to mindless

extrapolation. According to early predictions, all adult women by now should

be employed as telephone operators.

"Those who ignore the lessons of history are

doomed to repeat them." Taking this literally can be foolish. Time is the

great innovator. Consider each option on its own merits.

"We did that before and we got into trouble."

Yes, but (1) did we do it right? (2) If we had not done it, would we still

have gotten into trouble? (3) Even more trouble?

Don't forget, for every "because-of," there

is at least one "in-spite-of."

Thinking hypothetically in the past tense is

injurious to the mind. Thinking hypothetically about the future is all

you have.

The law of unintended consequences will always

prevail.

The futurist must think unthinkable thoughts

about social dislocations, about a world without petroleum, about nuclear

winter, about...

Malthus

How did Malthus go wrong? In 1798, he put forth

his theory that growth of population always outstrips growth of production.

Poverty is inevitable, he said.

One thing Malthus didn't know about was...

petroleum.

Find a twenty-foot wall. Preferably blank.

Mark off one-foot intervals along the floor. Each mark represents a century.

Over on the left you have the first Christmas. You can write "Magna Carta"

at a point twelve feet along the wall and "Columbus' Voyage" three feet

beyond that.

At about the eighteen-foot mark is Malthus

and his theory. Go seven inches further to the right. That's 1869, when

the first oil well was drilled in western Pennsylvania.

The significant growth in petroleum production

didn't begin until the twentieth century -- the nineteen-foot mark.

Take a pencil and start a line along the floor

right there. Bring the line up so that it is about ten inches above the

floor in the year 1950, a half-foot from the end of the twenty-foot wall.

Each vertical inch represents a million barrels

per day of petroleum production and consumption world-wide.

Bring your pencil nearly straight up to eighty

million barrels per day, six and a half feet above the floor. This should

occur about two inches from the right-hand edge of your wall, corresponding

to the end of the twentieth century.

Stand back and take a look.

You're seeing the shape of the "petroleum age"

in the context of history: a horizontal line signifying insignificance

for nineteen and a half feet, then bending to near vertical in just a few

inches. Imagine how many historical lines you can draw right on top of

petroleum consumption -- industrial output, technological development,

agricultural yield, population growth, economic prosperity.

Too bad Malthus couldn't have seen your wall.

Paradox

"You are sentenced to die within the next ten

days," pronounced the judge. "Furthermore, you shall not know in advance

the exact day of your hanging."

The prisoner was led away. That night he was

heard laughing and singing in his cell.

"What gives with the mirth?" asked his jailor

through the bars.

"Did you not hear the judge's proclamation?"

replied the condemned man.

"I was about to ask you the same thing," the

jailor said. "You're a goner, fella -- and in the next ten days, for sure."

"But I am not to know in advance the exact

day of the hanging. You heard the judge say that."

The jailor shrugged.

"You see, I cannot be hanged on the tenth day,

for the mere fact of my being alive on the ninth day would tell me in advance

that the tenth is the day chosen for the hanging."

Stepping closer to the jail door, the jailor

commenced a quizzical frown.

"If I am alive on the eighth day," the prisoner

went on, "I would then know that the sentence will most assuredly be carried

out on the ninth day, since the tenth day has already been ruled out. Thus,

my knowing in advance would violate the judge's order."

The jailor struggled to comprehend the prisoner's

logic.

"The ninth day having been eliminated along

with the tenth leaves only the first eight days for the hanging. In like

manner, however, the eighth day can be disqualified. And the seventh and

so on, back to this very day."

The prisoner smiled through the bars. After

a moment a light flickered in the jailor's mind.

"What you're saying..."

"What I'm saying," interrupted the prisoner,

"is nothing more than what the judge did say and thus caused to be law.

I am not condemned at all but must be set free, for the sentence cannot

be carried out."

"I think I get it," said the jailor at last.

"Good. Then join me in my song."

In a few days, six, to be exact, the prisoner

was taken from his cell and hanged. He had not known on the fifth day that

the next was his last.

Why the retelling of this old paradox?

Perhaps it can serve as a parable for the petroleum

age. Nature has pronounced a death sentence on the automobile to be carried

out before the gallon reaches $10.00. Motorists won't be allowed to know

in advance the exact price at which it will happen.

Rates of Change

Measuring the beginning of an "age" is easier

than predicting the end of one. What criteria -- technical, economic, social

-- should be used? One thing for sure: some time before the last drop of

oil is pumped out of the ground, the petroleum age will have come to an

end.

To make meaningful projections about the future,

it's usually a good idea to look at rates of change. For the case at hand,

petroleum is being used up at some "consumption rate." Meanwhile, petroleum

is being found at some ''discovery rate."

Consider the situation in which the discovery

rate exceeds the consumption rate. When that occurs, the size of the world's

petroleum reserves increases. For some time now, the opposite situation

has held. Consumption rates have exceeded discovery rates, and reserves

have been decreasing. Experts in the petroleum industry like to argue that

this doesn't necessarily mean the world is running out of oil.

Another type of calculation takes into account

the difficulty of finding petroleum resources. Of necessity, oil wells

are being drilled deeper year by year, at a rate greater than the discovery

rate. It's not easy to explain why this doesn't signal the approaching

end of the petroleum age.

One of the things that confuses matters is

the fact that it's not always possible to tell how much petroleum will

ultimately be pumped out of a new well. A preliminary estimate is all you

have. Years of pumping must go by before you know the actual amount.

Estimates, in the past, have been inaccurate.

Mostly on the conservative side. Actual production generally turns out

to be higher than the estimates. This would seem to be good news. However,

when you go back in history to the time of a discovery and replace the

low estimate with the higher actual, you cause a backward shift in effective

discovery rate. Meanwhile, the accuracy of estimating procedures has improved,

such that in the future, the backward shift will be far less.

The combined effect of these revisions is a

further diminution of the world's projected petroleum reserves.

And an earlier end for the petroleum age.

Equilibrium

In the post-petroleum age, all living things

must attain equilibrium with the earth's periodic ration of solar energy.

Consider the case of a family of four living

in the temperate zone. The post-petroleum age has begun and they are determined

to "equilibrate."

Solar heating of their home would not quite

keep them warm in winter, so our model family might make up the difference

by burning firewood. With access to a small forest, the family could cut

their own. They'd require approximately two and a half acres of trees in

order to ensure a continuous supply of firewood year after year.

For food, our model family might keep a garden

and raise some poultry. They could get along on about two and a half acres

of land. This allows for crop rotation, but petroleum-derived fertilizers

and pesticides would be ruled out by the equilibrium model.

Now, let's assume that one member of the family

commutes by motor vehicle five miles to work every day. An additional two

and a half acres would provide the requisite non-fossil fuel, grain alcohol.

Finally, it is reasonable to suppose that a

family of four will have other needs requiring the impoundment of even

more of the solar ration -- factory operations, health care, fabrics, paper,

community services. Figure another two and a half acres.

If these estimates are correct, about ten acres

of tillable land would be necessary to support a family of four in the

post-petroleum age. Thus, one can estimate the carrying capacity of a given

area. And the limits on population.

The use of bicycles for commuting might provide

room for 25% more people in the temperate zone.

By the way, the motor vehicle in the model

set forth above is not an automobile. To go ten miles a day on the yield

of two and a half acres of biomass, the daily commuter would be limited

to a moped.

MAIL

Scenario:

Two futurists meet in a park. One is a particular automobilist, A, the

other, a certain bicyclist, B.

A.

Have

you been thinking much about the future of the mails?

B.

No,

but your question implies that you have.

A.

Will

there be mail in what you have chosen to call the "post-petroleum age"?

B.What

do you mean by "mail"?

A.

Come,

now, we're using your native tongue. Must I make like a dictionary?

B.If

you mean "mail, comma, delivery of," it seems doubtful.

A.

Shall

we take that as our proposition?

B.Under

the doctrine that assertion carries the burden of proof, might it not be

more appropriate for you to frame the proposition?

A.

All

right. But perhaps you miss-spoke yourself with the word "proof." As usual,

we shall be talking about the future.

B.

To

be sure. We must reserve "proof" for a more rigorous context.

A.

Very

well, then, let us take as our proposition: "Resolved, delivery of mail

will continue, even in the 'post-petroleum age'."

B.

Still

seems doubtful, but go ahead.

A.

Mail

is an essential form of human communication. As long as there are documents,

there will be a need to deliver them from one place to another.

B.

Mind

an interruption?

A.

Already?

B.

"Need"

may well be a necessary condition for the perpetuation of a given technology,

but it is hardly sufficient.

A.

For

the moment, though, can you just accept the premise?

B.

No.

There's a technological revolution already underway, affecting all aspects

of information processing and communications. Your premise makes the questionable

assumption that "documents,” as we now know them, will survive this revolution,

A.

Worldwide,

they will. And for a very long time. Well into the "post-petroleum age."

Besides, except for smoke signals, no form of communications technology

has ever been completely replaced by a successor.

B.

Do

you really expect your position to prevail on the strength of historical

analogies?

A.

Not

at all. Even when every home has a computer terminal and every resident

knows how to use electronic mail, there will still be paper documents sufficient

to warrant the continued operation of the mails.

B.

What

kind of paper documents, junk mail?

A.

The

proper term is "third-class mail," and, yes, that will be one kind.

B.

Most

people today resent junk mail, though. Giving it up will be among the least

of the inconveniences in the post-petroleum age.

A.

Yet,

it facilitates a channel of commerce in the U.S. several tens of billions

of dollars wide. There's just a negative perception.

B.

Ah!

But, a perception is real -- or, if not real, more important than that

which is.

A.

You're

especially quick with the platitudes today, my bicycling friend. In the

past, you' ve argued that a perception can also be wrong.

B.

Your

retroactive concession is accepted. Proceed.

A.

For

the case at hand, if a person is not interested in the importunings of

third-class mail, that person has but to throw it away unread. You can

get rid of a whole week's worth in less time than it takes to endure just

one television commercial. And don't forget, unlike the newspaper, which

is mostly advertisement and contains just as much throw-away bulk, third-class

mail is free.

B.

There

must be more to people's resentment of junk mail than that.

A.

Indeed.

Disappointment. People open their mailboxes like a daily present, only

to have their expectations dashed by the discovery of bills...

B.

And

junk mail. Let's get back to technical matters. How feasible will it be,

after the world's petroleum is gone, to deliver tons of documents every

day?

A.

The

expression "every day" loads up your question with an assumption of your

own.

B.

You

mean the mail might be delivered less often?

A.

Why

not? My model for mail-of-the-future would have weekly rounds. Isn't that

often enough? For the urgent stuff, you'll have electronic alternatives.

Automated funds transfer systems, for example, will long since have taken

the "float" out of our banking processes, driving the effective velocity

of money to dizzying rates.

B.

Perhaps

so, but by what means does your model provide for the requisite hauling

of the remaining paper documents, however seldom?

A.

Let's

put the problem into perspective. The incremental energy required to deliver

mail is quite small.

B.

Can

you be more specific?

A.

You

are familiar, of course, with the term "boustrophedon"...

B.

Did

you just make it up?

A.

It

means "as the ox plows."

B.

Oh,

that boustro-... How did you pronounce it?

A.

The

mails are delivered in a singularly efficient pattern -- back and forth,

up and down streets, house by house. The way one mows one's lawn or the

way a librarian returns books to the shelf.

B.

Is

there any other way?

A.

There's

the "raster" -- the way you read a page. In raster mode, the post-person

would start at one end of a street, picking up and delivering along one

side, then dash back to the starting end before serving the other side.

B.

The

raster doesn't make any sense.

A.

The

“star" is even less efficient.

B.

Of

course it is. What's the star?

A.

Star

routes require separate trips from, say, the local post office out to each

delivery point. Don't laugh. Energy-intensive, star patterns have been

used a lot. Special delivery almost works that way. So do some package

delivery services. Not to mention pizza-parlors.

B.

Enough

specifics. How about some relevance?

A.

Consider

first what might be called the "reverse star." That's what suburbanites

use today for getting their groceries.

B.

By

any chance are you going to suggest that in the future, people will have

their groceries delivered by mail?

A.

It's

already been done. Until the middle of the twentieth century, in some European

countries where postal systems were far more de-centralized than in the

U.S., not only were groceries delivered by mail, but it was customary to

place one's grocery orders by mail as well. Often, the same day.

B.

You'

ve trapped yourself. That would have required more than one mail-round

per day. In your model, it would take two weeks to have your groceries

delivered.

A.

Not

at all. You've forgotten the telephone -- which is both energy efficient

and ubiquitous. With modem refrigeration and preservatives, you can get

along quite well with one delivery of groceries per week.

B.

Somehow

you seem to be ducking the main question. You haven't helped matters at

all by loading up the petroleum-deprived mails with groceries...

A.

And

a lot of other things, while we're at it. Catalogs published even today

offer for sale almost any product imaginable through the mails. Your question

is indeed still pending, though. Patience.

B.

The

suspense is bearable.

A.

As

an order of magnitude, the annual postal revenues are $17 billion in the

U.S. There are about 87 million households, or postal delivery points.

Performing the indicated division, you get about $200 per year for each

delivery point.

B.

How

much petroleum is consumed?

A.

This

may surprise you. Only about 6% of the total postal expenses are attributable

to gasoline and diesel fuel. That's about $12 per year per delivery point.

A buck a month per household.

B.

It's

because of that fancy word

A.

Boustrophedon.

Converted to gallons, the postal service must burn less than a gallon per

month on behalf of each household. The individual delivery is really some

fraction of that. What's needed is just the incremental energy to get from

your neighbor's house to yours each day.

B.

And

in your mail-of-the-future model, you' ve postulated weekly deliveries,

a reduction by a factor of one-sixth in energy consumption.

A.

It

comes down to less than an eighth of a gallon per month. Even my little

compact car, commuting 5 miles per day, consumes more than one hundred

times that each month.

B.

You

still need a lot of postal vehicles running around.

A.

Yes,

but at these very low incremental consumption levels, are there not several

alternative energy sources that qualify to propel them?

B.

Your

model postulates more decentralization of the mails, does it not?

A.

Along

with nearly everything else, yes.

B.

Well

then, biomass comes first to mind. Methanol, whatever.

A.

Also,

you might consider wind-generated electrolysis of water and hydrogen powered

vehicles.

B.And one

more idea.

A.

I'm

wincing.

B.

The

bicycle.

Experiment

In April 1972, a certain bicyclist began a

five-year personal experiment. The idea was to see what it will be like

to live in the post-petroleum age.

The simulation required making a number of

changes in life-style, including the following: adapting to a vegetarian

diet, eschewing canned goods and other forms of throw-away packaging, wearing

natural fabrics, installing a clothes-line, purchasing as much as possible

from catalogs, and accepting mail delivery only once per week.

The most important part of the experiment was

renouncing the use of an automobile for the daily, five-mile trip to the

office" Just by riding a bicycle, it was possible to eliminate the largest

individual use of petroleum.

Here's some advice for the bicycling commuter.

If you're going to commute on a bicycle, you

have to make preparations. For example, since leather shoes slide right

off the pedals, you'll want to wear some sport shoes on the bike and change

into your wing-tips at the office.

That's just the beginning. You need to take

a systems approach. For all-weather commuting, most of your wardrobe will

have to change. You may wind up performing a sartorial metamorphosis every

morning and evening. Particularly in summer. In winter, you need the equivalent

of ski togs on the bike. For rain, get a sailor's foul-weather outfit.

Your bicycle will need special equipment, too.

A luggage rack and bungies will let you carry your briefcase. Try strapping

on removable saddle bags for your fresh underwear, socks, and shirts. Don't

forget a generator-powered headlight. It gets dark early in the winter.

You're all set. except for a portable radio

for the morning news.

At the end of five years, including four exceptionally

snowy New England winters, there were only two problems to report. Neither

will be factors in the post-petroleum age. The first problem was the embarrassment

of showing up at work dressed like Captain Marvel.

The second problem was breathing automobile

exhaust -- the ultimate flatulence.

Future as History

Not all bicyclists are futurists. Some might

be called "past-ists." No matter. The post-petroleum age will be quite

a lot like the pre-petroleum age.

There'll be some important differences, though.

Our telephones -- we'll still have them. You

can make 75,000 transcontinental telephone calls for the energy equivalent

of a gallon of wood alcohol.

We'll keep television, too. But our sets will

be smaller.

The clothes dryer will have to go, but the

electric razor won't.

Indoor plumbing will continue in common use.

Central heating, however, will be a problem

in colder climates unless we give up windows.

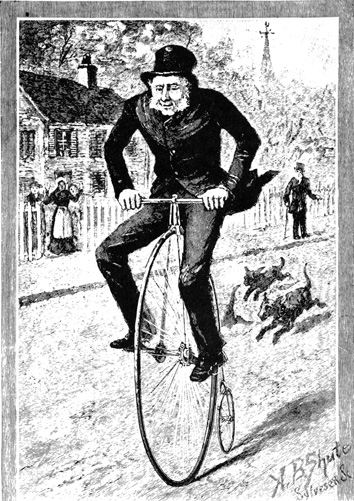

The bicycle will return as the most practical

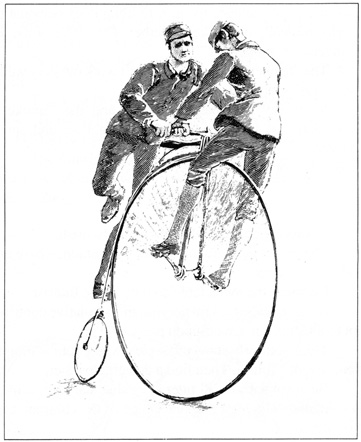

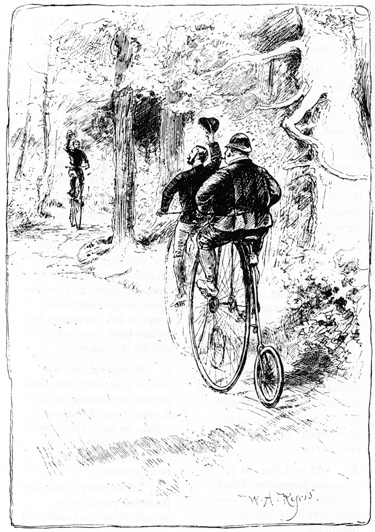

form of adult transportation. Not the high-wheel bicycle, sad to say. There's

something majestic about those old contraptions.

Ask any past-ist.

|