Two Birds

with one Stone

Sometimes the compromise is too much. Try to imagine a Jaguar stationwagon.There is no convertible truck. But there is the amphibian airplane. Bill was a public relations staffer in our California office. He was thinking about buying an amphibian. He called me, the only pilot he knew, for advice. It was May of 1971. Living as a corporate nomad in Connecticut, I spent a week a month in Los Angeles. Two-Four Fox was still in its hangar at Torrance. "Why an amphibian, Bill?" I asked over the phone.

"Like Big Bear, Arrowhead, what?" "The 'Lake'," said Bill, correcting my misunderstanding. "Single engine, 175 horsepower." "It's a design compromise," I said. "An amphibian does not fly as well as an airplane or float as well as a boat." "Want to fly the Lake and tell me what you think?" "Tomorrow soon enough?"

I grabbed the red-eye from New York. My son Harv, then thirteen and utterly nonchalant about flying, was nevertheless eager to go along that Saturday morning. It would be his first time in an amphibian, too. We picked up Bill at the Santa Monica Airport in Two-Four Fox. Off we flew to the Long Beach Airport for our meeting with a fellow I'll call Ronald. And the Lake. In his deck shoes and captain's cap, Ronald, a balding man in his thirties, looked the part of a boater more than an aviator. He was waiting for us on the tarmac and guided Two-Four Fox into a tie-down next to the Lake. Bill had told me that Ronald was just getting started with his dealership and did not yet have a sales office. Upon seeing the Lake for the first time, I could think of no better word than 'nifty.' The fuselage, which doubles as a hull, resembled the shape of the Catalina flying boat from the forties. Its canopy offers an unobstructed view ahead and above. Fixed pontoons -- called 'sponsons' -- adorn the mid-wing. The engine nacelle stands above the fuselage on a pylon facing aft. Just sitting there on the ramp, the Lake gives you the feeling of elan. You would have to be a dreary person indeed not to admire its multipurpose design. Ronald reminded me of closely barbered Ringo Starr, without the Liverpudlian accent. "The Lake is a fine machine," said he while shaking my hand, then nodding to my son, "for the whole family." He strolled around the plane performing a pre-flight inspection, all the while pointing out features -- killing two birds with one stone, as it were. Bill snapped pictures. My son and I followed along. "How fast?" asked Harv. "About like the Cessna 172," answered Ronald. "Having the engine perched atop that pylon makes this one of the quietest single-engine aircraft in production." "Gotta fly this little beauty," I said.

Ronald opened

the canopy and gestured for me to take the left seat.

Bill and Harv climbed

in, and alarm bells began sounding inside my head.

While Ronald was setting up the radios, I chanced to see that the Gear-Down light was not illuminated. Ronald watched as I reached toward the lamp holder to operate its push-to-test switch. I was surprised that it was warm to the touch. The mechanical iris was stopped down for night flying. Twisted open, it revealed the bulb shining bright green. Ronald shook his head. "You won't need that," he hollered. The engine was not that quiet after all. "Look." Ronald pointed past my nose. A convex mirror on the left sponson reflected a curved image of the whole airplane including all three landing gear. Ronald re-closed the iris. "I never trust electric indicators," he said. Long Beach Ground directed us to Runway Two-Five Left. Our run-up was performed from Ronald's memory. The engine controls are overhead, which gives the Lake some extra charm. On the runway, I reached up and swung the throttle lever forward, and our engine went to work at 2,500 RPM. Off the ground and climbing. Ronald gave me a thumbs up. I operated the gear handle and watched the reflection in the mirror while the gear was sucked up and the doors over the nosewheel closed. "You're aboard a flying boat now," Ronald shouted. We departed the pattern for the Long Beach Harbor. For the next thirty minutes I performed gentle maneuvers to get the feel of the controls. The time was coming for my first water landing, and I was excited as hell. Ronald pointing to a strip of water. "Let's give it a go, along there." We let down and set up a landing pattern. I scanned the area for boats and logs, then lowered the flaps. Ronald talked me through the landing. He had me keep some power all the way to touchdown. Then I eased back on both the throttle and yoke as the hull planed over the water like the ultimate speedboat. The Lake stopped quickly and we sat rocking for a moment while our wake caught up with us. "Is this bitchin' or what!" I hollered over the sound of the alarm bells in my head. "Everybody should have one of these, Bill." My son allowed as how it was cool. Bill smiled into his viewfinder and clicked away, as boatloads of waving people passed nearby. Ronald deployed the water rudder. I turned the Lake around and motored away from the breakwater toward our starting point. "The Lake," Ronald exulted, "goes wherever and whenever you want to go. As you see, the Lake does not require an aerodrome." Ronald's got another prospect and is moving in for the kill. Two birds with one stone. "Tell me about water takeoffs," I said. "Your first objective is to elevate the hull out of the water like a water skier. To do that, you hold the yoke all the way back and apply full power." I brought the amphibian around into the wind, and Ronald stowed the water rudder. "Once the Lake is planing the water," he continued, "let the airspeed build up to about 50, then pull back again to break free." The four of us were all smiles as I pulled the control wheel against my chest, reached up and shoved the throttle all the way forward. The engine came to life at 2,500. Something was wrong. We went underwater immediately.

"Let me try it," said Ronald. I looked over my shoulder at Bill. He was holding his camera away from the dripping water, not smiling. Ronald did exactly what I did. The Lake did exactly what the Lake did. We could hear the engine up there laboring away, but we were not going anywhere but down. Ronald shut off the engine. We sat rocking in silence while seawater poured off the canopy and into the cabin. "I think I know the problem," said Ronald, cheerfully. "The nose gear doors, surely." He opened his side of the canopy, unfastened his seatbelt and stood up. "You won't go away now will you?" he said. The three of us were not amused. Ronald climbed out onto the nose of the plane. "Forward of the cockpit, you see, we have the bow of your boat. With the Lake you also have a right handy vessel." Ronald reached down into the water to feel the doors that cover the nose gear. "Just as I thought, they didn't close completely." With the bells inside my head silenced, I began to look around for a place to disembark. Maybe one of those boats full of gawkers will tow us ashore. Despite his marketing aplomb, Ronald was losing both prospects. "And, as is the case with a family boat," Ronald went on, "you occasionally have to perform maintenance duties." With that he began pulling abruptly with both hands on the nose wheel doors. "Clunk," went the nose wheel doors. "Clunk, ca-lunk!" "There!" exclaimed Ronald, sitting up on his knees. "The linkage requires adjustment. I'll see to it upon our return." Ronald shook the water off his arms and climbed back into his seat, grinning over his shoulder at Bill. "If you had only brought your tacklebox," he chuckled, "you might then have demonstrated your angling expertise to Master Harv here." Bill had not said much since we left Long Beach. He seemed utterly disinclined to talk now. Ronald signaled for me to crank up the engine again. He sat back confidently while I prepared to attempt another take off. Pull back, full power. Presto, we lifted up out of the water. The Lake began to be fun again. I relaxed the controls and let the speed build up. It took a whole lot longer than I expected. I looked across at Ronald. He was concentrating on the breakwater ahead, the smile gradually disappearing from his face. At 50 knots I pulled back and we hopped off the water, then settled immediately and bounced. Again we lifted off and mushed back down. The breakwater was getting close. If we did not stay aloft on this bounce -- hey, I didn't want to think about it. The Lake barely cleared the rocks. I could see into the faces of startled fishermen passing immediately beside us, pulling their poles aside. Waves in the open ocean reached up to slap our hull, as if to chastise an intruder. One more slap and we dribbled into the sky. It was for such a time that the word

'whew' was coined.

Ronald stared out the window, shaking his head and

grimacing.

Just then, I heard static, followed by a few syllables. "--craft, calling Long B-- ... --report downwind for Run--" Better than nothing. As we entered the downwind leg, I lowered the gear. The Lake indeed handled about like a Cessna 172, only heavier now. Maybe that was because the thing was loaded to the Plimsol mark -- with the water on the inside. On a routine GUMP check, I eyeballed the Gear-Down light. It was dark. I touched the light holder. It was cold. I opened the iris. The light was not on. I operated the push-to-test switch. The light came on, bright green. A quick glance out the left window and I could see the main gear fully deployed. I squinted at Ronald's convex mirror out there on the left sponson confirmed the indication. The nose gear had not come down.

The tower cleared us to land. The

radio, at least, was

working. I acknowledged the call as we turned final.

I debated in my mind about how to break the news to

Ronald and our passengers.

So here we are, descending through 500 feet with a stuck nose gear. Determined to make the most of this opportunity, I have decided to kill two birds with one stone. "Ronald," said I, "tell me again about that Gear-Down light." He wrested himself from his funk and grinned. "Well, I never trust it. Have a look at the mirror out there on your sponson..." Suddenly Ronald's chin plummeted toward his deck shoes, his eyebrows sought refuge under his captain's cap. "Oh my God! Pull up!" Already grasping the overhead throttle lever, I hollered over my shoulder, "Hey Bill, give me your camera. Let me see if I can get a picture of the mirror on that sponson out there." I looked back at Harv and winked. "Looks like we'll be taking another speedboat ride, Son." I powered up and continued to fly along the runway.

Ronald grabbed the microphone and shrieked at the tower about our problem. He frantically cycled the gear up, down, once, twice. I turned crosswind and we climbed back up to a thousand feet. "If our problem happens to be in the hydraulics, Ronald, playing with the undercarriage that way could leave our mains stuck hanging out." Face ashen, Ronald slumped back in his seat. The controller at Long Beach invited us to fly a low approach past the tower so they could train their binoculars on us. "Your main gear looks good," said the tower operator, "but the nose gear is not showing at all. No sign of hydraulic leak." I retracted the gear. The yellow, Gear-Up light came on. "Will you be needing emergency equipment," asked the controller? I pulled up and banked left again. "Tell 'em we'll put down in the harbor, Ronald." Out of habit, the controller recited the altimeter setting and wished us luck. Flying over the city of Long Beach, I

turned my head and

received an approving smile from my son. It was one of

those moments.

"Fine, old chap -- if we had all our wheels," I said. "Let's go to Cabrillo Beach. It's sand, not concrete. I don't want to scuff up your hull." Ronald shrugged. I looked back at Bill. "We can kill two birds with one stone: fix the nose wheel doors and ogle the chicks on the beach."

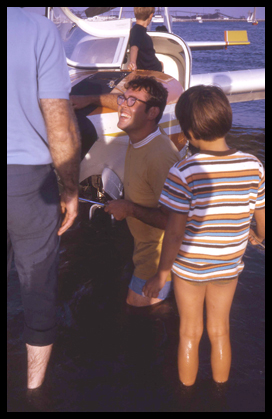

Bill's camera was clicking as we felt

the sand against

the hull. There must have been a dozen kids splashing

toward us, all colors

and nationalities. They jumped onto the wings with

their bellies.

Ronald sighed and opened the canopy. The four of us

climbed out and waded

ashore, where we were greeted by a handful of cheering

youngsters, all

immortalized in the pictures you see here.

Ronald put the gear down. Only the two main wheels dropped out of the wings and splashed into the water. Bill climbed onto the stabilizer which lifted the nose out of the water. A bunch of bathers helped us shove the Lake forward. The main wheels rolled onto the sand. A bespectacled man named Ed beached a boat full of kids nearby and strolled up to offer his assistance. An IBM field engineer, Ed brought a box of tools from his stationwagon. "We could build a damn airplane," he said with a grin.

Ed, Ronald, and I worked all afternoon on the nose gear. Each time we wanted to cycle the gear for a test, we had to round up helpers to roll the plane back down the beach into the water.

Something in the door linkage was hanging up. It was possible to get the nose gear down only by preventing the doors from closing completely. Just before dusk, I hit upon an idea. I found a piece of foam rubber and squeezed it into the linkage so that the door was held open...

...by a fraction of an inch. It worked. With its door held open, the nose gear would indeed come down. We tested it three times with the plane in the water. Whether it would work after the pounding of a speedboat take-off was another question. My strategy was for Ronald to take the plane off and immediately drop the gear. If the wheels all came down -- and showed a green light -- he would fly gear-down back to Long Beach Airport. Bill, Harv and I would take a cab. If the nose wheel failed to come down, Ronald was advised to put the gear up and land in the water again. The plan was for him to water taxi to a nearby marina and park the plane overnight as a boat. "Don't you chaps want to come along?" asked Ronald. I shook my head. "With the nose-wheel door ajar, your Lake acts like a goddam submarine! Better that you take off as light as possible." Ronald climbed into the Lake and started the engine. About then the police showed up.

Two burly cops got out of their patrol car and marched down the beach. By then, the Lake was bobbing around with Ronald retracting the gear against the foam-rubber stop. "What's going on here?" asked one of the officers. "Nose gear stuck," said Bill, the PR staffer. The cops consulted their manual. "Let's see: 'airplane, crash'? no; 'airplane, stolen'? no -- nothing about a 'nose gear'..." The Lake water-taxied out into the bay and turned toward us. As the engine revved, the cops became alarmed. "What's he doing now?" Harv, the noted aviation expert, explained the situation to the authorities, complete with estimated aircraft weight and requisite take-off distance against the prevailing sea breeze. My son's predictions proved accurate enough. The Lake popped up and flew over our heads. We craned our necks and watch the wheels -- all three -- coming down. The crowd on the beach including the cops cheered. Ronald rocked his wings and turned toward Long Beach Airport. It was then that Bill and I discovered we had left our shoes and wallets in the Lake. Bill, shivering in the evening sea breezes, explained our predicament to Ed from IBM and offered him a set of pictures in exchange for a ride to the Long Beach Airport. For the first time all day, Bill used complete sentences. "Los Angeles at night is a fabulous sight," I told Ed. "You are invited to ride along while my son and I take Bill back to Santa Monica." Ed grinned. "We can kill two birds with one stone." The three of us crowded into Ed's stationwagon with his sunburned wife and crabby kids for the long ride to their home in Inglewood. There we spent an hour helping Ed wash down his boat. About 9:00 P.M., Bill, Harv and I finally arrived, barefoot and hungry, at Ronald's tie-down. Wearing his deck shoes and captain's cap, Ronald stood leaning against the wing of the Lake in the dark, pantlegs still rolled up. He handed us our belongings. "Did you mean what you said about purchasing the Lake?" Ronald asked me. He was serious. "We'll get back to you on that, Ronald." |

"Fishing,"

he answered. The best PR guys try not to say much.

Bill was famous around

the plant for his fly-fishing and for his photography.

His office walls

were covered with framed photographs. Bill looked

strange standing in a

river without his three-piece suit on. "Been looking

at a 'Lake'," he said.

"Fishing,"

he answered. The best PR guys try not to say much.

Bill was famous around

the plant for his fly-fishing and for his photography.

His office walls

were covered with framed photographs. Bill looked

strange standing in a

river without his three-piece suit on. "Been looking

at a 'Lake'," he said.

The

water near Cabrillo Beach was dotted with boats and

streaked with water

skiers. We made one low pass as a signal of our

intention. Then I set up

an approach into the wind. My second water landing,

which was just as exciting

as the first, did not merit a fanfare. All four of us

were simply glad

to have our fannies on the ground -- or in the ocean,

whichever the case

may be. Ronald regained his composure and put down the

water rudder.

The

water near Cabrillo Beach was dotted with boats and

streaked with water

skiers. We made one low pass as a signal of our

intention. Then I set up

an approach into the wind. My second water landing,

which was just as exciting

as the first, did not merit a fanfare. All four of us

were simply glad

to have our fannies on the ground -- or in the ocean,

whichever the case

may be. Ronald regained his composure and put down the

water rudder.

My

son,

ever nonchalant, stood in the Lake's cabin and began

making new friends,

while Ronald and I made the first of many inspections

of the nose-gear

mechanism.

My

son,

ever nonchalant, stood in the Lake's cabin and began

making new friends,

while Ronald and I made the first of many inspections

of the nose-gear

mechanism.