|

Bumps

Ever thought much about speed bumps?

The first ones showed up in driveways near

schools and playgrounds. Like some roadway epidemic, insolent concrete

hillocks have infected all sorts of places: shopping centers, airports

-- even factory parking lots.

We know what causes speed bumps, but what do

they mean? The automobile, sad to say, is but a means to an end. Driving

has become a joyless, parenthetical function. Incarcerated inside their

cars, motorists by the millions are sentenced to daily intervals of stultifying

boredom as they move themselves along from where they were to where they

want to be.

Getting there used to be half the fun. What

happened?

Inactivity numbs the mind. Impatience drives

off nobler attributes: piety, generosity, understanding. Thus, the motorist

may be fully capable of reading a traffic sign that mandates a speed reduction,

and yet be incompetent to comply. That's the consequence of the dulling

and deforming of the driver's vital mental acuity.

Direct mechanical interferences, such as afforded

by speed bumps, may be the only practical way to communicate with the motoring

mind. A speed bump, after all, tells you in no uncertain terms that if

you don't slow down, you'll bring injury to your own suspension system.

A sign, on the other hand, can only warn in abstract symbols that you might

bring injury to somebody else's child.

Seems a shame to lumpy up a perfectly smooth

roadway. Not only that, but for the exceptional driver who is actually

capable of obeying signs, speed bumps must be an insult.

For the bicyclist, speed bumps are no problem.

There's always a smooth drainage gap along the side.

Dumb

Bicycles are dumb -- in the physiological sense.

They hardly make a sound. But bicyclists are not deaf, usually. You can

communicate with bicyclists from the comfort of your own car. And you don't

need a fancy citizens' band rig, just your hom.

Admittedly, your honking vocabulary is limited.

To help avoid misunderstandings, here is a lexicon of the expressions heard

most often on the nation's roads:

A simple short honk ("beep") means, "I see

you," when sounded from a reasonable distance and, "Watch out!" when expressed

right beside the bicyclist's ear.

A long honk ("BLAAGH!") from close up means,

"Get over into the ditch with the broken bottles where you belong!"

A long honk from far away ("blaagh") means,

"For heaven's sake, give me lots of room. If it were not for this power

steering, I'd be completely out of control."

A double honk ("beep-beep") means, "Hello there,

biker. What a nice day for a ride."

Joggist

Many bicyclists are joggers. The reason may

surprise you

Bicycling is not that much exercise. It's too

efficient. Bicycling is six times more efficient than running. That means

you have to ride at least six times further than you would run to consume

a given amount of energy.

But you'd be traveling only three times faster.

A daily five-mile run takes less than three-quarters of an hour and is

roughly equivalent to a thirty-mile ride, which would require some two

hours -- more time than most people have for exercise.

So bicyclists have to jog to stay fit. Somewhat

like motorists.

Parking

Let's clear up a misconception.

Bicyclists are in favor of more abundant parking

facilities in down town areas, whatever the costs.

Parking is one of the best things to do with

cars. A well-parked stationwagon is far less troublesome than one which

is out swerving and loping all over our roads.

By the way, it is not true that you can park

16 bicycles in a single automobile parking space. Twelve is more like it

Pie

Skip this if you're not watching your weight.

Bicycling does bum up some calories. Not very

many though.

A daily commute of 30 minutes each way amounts

to less than a piece of pie a day.

Work-For-All

Suppose you work five days per week, eight

hours per day.

One day you decide to get rid of your automobile

and ride a bicycle to work. At the same time you persuade your boss to

let you work 10% fewer hours: four days a week, nine hours per day -- in

exchange for a 10% cut in salary.

Your pay per hour stays the same. So does your

spendable income, as a result of the automobile expenses you're saving.

But you have an extra day off each week.

Now, suppose a lot of people decide to do the

same thing. The boss soon finds her/himself shorthanded and must hire 10%

more people to get the same work done. Why. if the bicycling idea became

popular enough, there'd be a widespread labor shortage.

So much for unemployment.

Pot-Hole

The pot-holes in our city streets and country

roads are adequate. We have plenty of them. It seems unnecessary to put

in more.

The problem is, pot-holes are no more effective

than our traffic laws in limiting the speed of our motor vehicles -- thanks

to steel-belted radials and polyglass brains.

You'd think our suburbs were practice courses

tor the Baja Badlands Race the way some folks drive.

Why, if it were not for those pot-holes, bicyclists

wouldn't have a chance. But let's not invest a lot of public moneys on

new pot-holes.

A few more "Bike-Way" signs might help, though.

Bonus

Suppose you commute on a bicycle 30 minutes

each way. You spend 200 hours on your bicycle each working year. You do

this throughout your working life, from age 21 to your retirement at 65.

You will spend a total of 8,800 hours commuting on a bicycle. Divide that

by 24 and you get 367 days or one full year on your bicycle in 44 years

of commuting.

So you're spending an hour a day pedaling a

bicycle. You're healthier than a person who does not. You'll probably live

longer. You'd go around the office making a convincing argument about how

you've added at least a year to your life expectancy. A year added to 70,

you'd say, is a mere 1.43% increase -- a cinch to justify.

But there's more you can say. That 30 minutes

each way on a bike would require at least 10 minutes in a car. Thus, your

net cost for the extra year of life is not a full year but only 244 days.

You'd realize a 50% bonus on time invested.

That's not the bicycle commuter's real bonus,

though. You'll want to save that term to describe the extra fun you're

having each day.

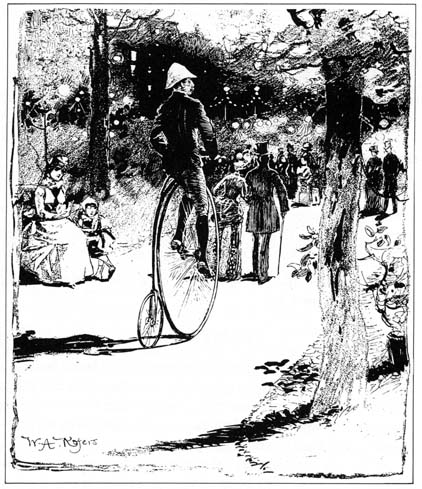

Subjective Speed

Speed is a derived quantity. You get it by

dividing elapsed time into distance traveled -- or words typed, pages read,

cotton picked, parts sorted, whatever.

"Objective speed," you might call it.

"Subjective speed" is also a derived quantity.

You take perceived time and divide it into

events experienced.

Interesting activities, of course, reduce our

perception of the passage of time. Hours can seem like minutes. The result

is a faster subjective speed than what you experience with dull activities.

That's probably why the subjective speed of

a bicycle is so much faster than that of an automobile.

Better not let subjective speed fool you, though.

Clocks and watches measure elapsed, not perceived time. If you don't want

to be late, leave a little early when you go zipping -- subjectively --

across town on your two-wheeler. |