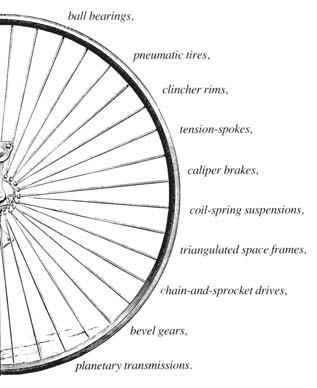

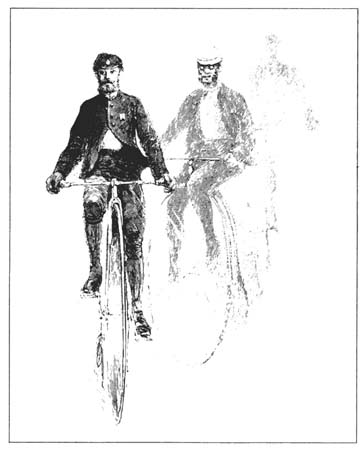

Are these simply balms to soothe the technologized spirit? Even so, haven't you wondered what that "100 inches" is all about? The bicycle, as it first appeared in the beginning of the 19th century, had no pedals. How slow and awkward this "draught" vehicle must have been, drawn along by action of the rider's feet against the roadway. More than fifty years went by before pedals were invented, after which the bicycle became what it is today, a "locomotive." Pedals lifted the rider's feet from the ground, and speed increased somewhat. Pedaling rate set the limit in those early days. It still does. You can only crank those pedals so fast. Early designers found that for a given pedaling rate, higher speeds could be achieved by making the drive wheel larger. Thus, the high wheel bicycle was invented. Better known as the "ordinary" in the 1880s, the bicycle grew in size and picked up more speed -- the limit this time determined by the length of the rider's legs. Ordinaries were often custom-made to fit the rider like a pair of shoes. Wheel diameter became an important specification. It was traditionally given as the first name in identifying a particular bicycle: 52-inch Rudge, 56-inch Victor Roadster, and the largest ever built, the 64-inch Columbia Expert. The back wheel, meanwhile, shrank away to save weight. The machine was fast and majestic. It was also dangerous and unforgiving. Along came the chain-and-sprocket drive. The pedal crank was taken off the front fork and given an axle of its own in the middle of the bicycle frame. Propulsion came from the rear wheel by means of the chain. It was 1890, and the "safety" was born. A few early safeties were actually built with a large wheel in the rear. Soon somebody noticed that the sprocket on the pedal crank and the sprocket on the drive wheel did not have to be the same size. For example, the bicycle designer might consider putting a large sprocket on the pedal crank and a small one on the rear wheel. There was an advantage in doing so: to be fast, the bicycle didn't need a big drive wheel anymore. The speed of the safety depended more on relative sprocket sizes than on the diameter of the drive wheel. The rear wheel then shrank back down to about the size that we see on today's "safety." Our question is still pending: What about those "100 inches?" We're coming to that. Some unit was needed to specify the "speed" of the safety. It wasn't so obvious anymore. One couldn't tell very much from wheel size. Measuring sprockets was unhandy and not meaningful -- particularly to long-time riders of the traditional, high-wheeled machines. What could be better, somebody must have thought, than expressing the safety's speed in ordinary terms? That's what the "100 inches" means -- the equivalent wheel size of an ordinary bicycle. You might like to figure this out for your own bicycle. First, count the number of teeth on your front sprocket. Let's suppose you get 36. Divide that by the number of teeth on your rear sprocket, 12, say. Now multiply by the diameter of your rear wheel, which is usually 27 inches. The result, 81 in this example, is in inches. It represents the wheel size of a nineteenth-century ordinary, equivalent in speed to your bicycle. The modem ten-speed safety offers the rider a dynamic

selection of sprocket combinations, representing various ordinary wheel

sizes, which range from under 20 inches to over 100 inches -- larger and

faster than the highest ordinary ever built.

That's the answer. Here's the question:"What do golf and jai-alai have in common?"

In the 19th century, bicyclists took their clothing seriously. Light weight leather shoes, long stockings, knickers tight around the thighs, ruffled shirt and tie, brass-buttoned coat with a small collar, and pith helmet or short-billed cap. All without a smile. One of the hardest things to master when learning to ride an old-fashioned, high-wheel bike is the wearing of a solemn countenance. The world all around you will grin unashamedly at the sight of you and your ordinary gliding majestically along the road. But you must not smile. That wouldn't be authentic.Or would it? None of the old photographs show smiling bicyclists --

nor anybody else smiling, for that matter. And for good reason. In the

19th century, photographic emulsions were so slow, that subjects were commonly

required to hold rigid poses for upwards of a minute. Just try to maintain

a genuine-looking smile for that long. It might be supposed, therefore,

that riders of the high-wheelers went around smiling all the time -- except

for when they were being photographed. Pictures of smiling bicyclists had

to wait for the sensitive films of the 20th century. But by then the ordinary

was being replaced by the chain-driven safety -- and knickers by long pants.Until

"pedal-pushers" came along.

That's the answer to another question. Here's the question: "What is unique about clothing styles in the 20th century?

The bicycle gave us...

The bicycle gave us… the automobile. Felicitations to the originator of the "Auto-Way" idea. A 19th century cartoon shows a harried homemaker washing clothes in a tub, with small children underfoot -- while his wife rides away on her bicycle. The caption: "Don't get the clothes too blue." Recommendations have been voiced by bicycling zealots that top-heavy pickups, macho vans, and stud-tired stationwagons should be banned to protect our roads. |

|

|

|

|