The next week, I was all set to make an

offer on Baron

Six-Three Niner-Seven Lima.

Someone handed me the phone, saying it

was my broker.

I frowned at the clock. Must be trouble.

Not trouble after all. I exhaled

and took a sip

of Gentleman Jack, grinning at my guests.

There were plenty of ways I might have

assessed the impact

of that conversation with Pete. However, my ego

was on autopilot.

The following exchange would cost me the full purchase

price of the Baron:

At that hazy moment, I had no idea how a contract in frozen eggs was structured. All my trading was in potatoes. Not eggs, not pork bellies, not grains, not metals -- potatoes, damn it! The next week, instead of buying the Baron, I took a bath in eggs.

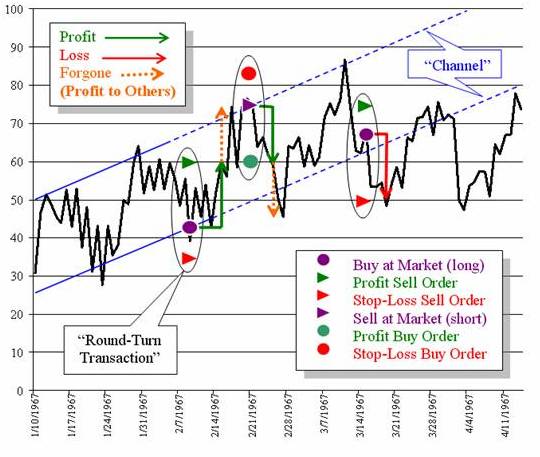

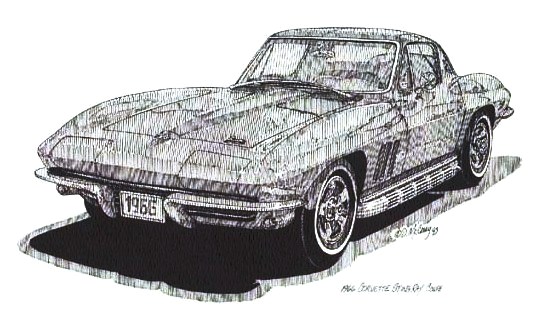

Thus, with peace of mind, I was able to spend weekends flying my family all over California in Two-Four Fox -- oh, and shopping for my next airplane, a Beechcraft Baron. Commodity Futures The stock market in the sixties was not being good to me. My mounting losses ranged from National Video and Murray Ohio both clobbered by Pacific Rim competitors respectively in color television tubes and cheap bicycles. Astroturf was the precursor to an immense market for outdoor carpeting. Or so I thought. Of course, I blamed my broker. About that time a distant relative named Pete began a new stock brokering career and prevailed upon me to open an account. In a packet of pamphlets he sent me were tutorials about commodity futures. Today, informative references are available on the web (see for example Investopedia). One evening of study in 1967 and I became captivated. The contrast with owning common stock in a company was striking. Stock prices are often decoupled from the business performance of the company. I never liked that. Indeed, some investors pay no attention to the 'fundamentals' of a business and instead go about making wagers with each other based on 'technical' aspects of the stock price itself. In sharp distinction from that paradigm, a 'speculator' in commodity futures derives his or her compensation by taking business risk, thus providing a vital service for commodity stakeholders, the "hedge."

In concept, a farmer and a potato chip producer might get together and negotiate a contract with each other, thereby assuring a mutually acceptable price. The farmer would then be committing to supply some quantity of potatoes at that price after the harvest and the potato chip producer committing to buy those potatoes when harvested. Such a static, one-on-one model is not practical. Commodity trading is best accomplished in many-to-many transactions. Commodity exchanges address that reality. Moreover, future prices are dynamic, as forecasted supplies and estimated demands fluctuate over time. For illustrations

see hypothetical scenarios.

|