|

Santa Monica Omni Internet

Version 2.0 Copyright

© 2012 by Paul Niquette. All rights

reserved. "Are you all right, Roy?" His gaze is fixed on the clouds ahead of us. The engine

labors into a climb.

Our little plane is banking to the left. "Roy, are you sick or what!" He was pale before take-off, now ashen. Roy seems

to be holding himself up with the control wheel,

staring, eyes glazed.

He turns toward me,

his lips are the color of bruises. "Paul." "Come on, Roy. You gotta

fly this

thing!" He nods grimly. The plane

banks more, still climbing. All at

once, Roy lets go of the control wheel and slumps to

the side. "What's wrong with Roy?" his wife asks from

the back seat. Continuing to turn left, we heave forward

toward the ground two miles below, speed increasing. The wheel

in front of me jerks toward the control panel. Grab it

with both hands and pull back. "Whoa,

goddam it!" The

engine growls.

I feel heavy in the seat. "I think he passed out, Mildred." The clouds ahead make a crazy angle with the

sky. A

quick glance at Roy.

His head is pressing against the side window. Now the

plane is nose-heavy.

I see why:

Roy's wife has leaned forward, reaching over

the front seat, shaking Roy’s shoulder. "Sit back, Mildred! Please!" "Maybe it’s his heart, Paul. We need to

get him to a doctor."

This is not how the flight was supposed to

be! Roy

passed out and next thing I know I am holding the

control wheel. As

Mildred moves back into her seat, I can feel the

plane coming into balance again. Bring the

nose up. "Can I just put his sweater over him?" “Not now.

Let me get this thing straightened out.” My wife is sitting beside Mildred. She must

be frightened.

To see her face, I have to turn around in my

seat. Annie

looks worried more than scared. Facing

forward again, I see the plane is banked to the

left. Why

the hell does it keep wanting

to do that? My

hands seem to be fighting each other. "Okay, Mildred. But take

it easy with the sweater."

Roy took his place in the left seat of the

plane and handed me a map. "Don't

call that a map," he said. "It's a

chart." Our wives were seated behind us, getting

acquainted. Roy and I had never socialized before. He frowned

at the gauges and started the engine. I examined

Roy's marks on the chart. He must

have laid out a dozen ‘check-points' along our

flight path from Santa Monica, California to Las

Vegas, Nevada.

I watched Roy steer the plane with the

rudder-pedals as we taxied to the side of the

runway. He

exercised the engine, then

mumbled something into the microphone. The

control tower answered promptly. "Eight-Three

Charlie, cleared for

take-off." Roy pushed in the throttle, a round knob in

the center of the control panel. The engine

took up the challenge and began pulling our little

plane along the runway. Roy eased

back on the control wheel and the concrete fell

away. While

climbing over the city of Santa Monica, Roy banked

the plane to the right. At

the shoreline, I turned around in my seat and

pointed out Pacific Ocean Park to my wife. I heard

her tell Mildred that we had taken the kids there

only a week ago. Roy's wife was something of a surprise to

me. Mildred smiled easily and spoke with precision. Quite a

contrast to her husband. Roy told

me that he never “bothered with no

colleges.” He

said his wife had enough education for the two of

them. The engine filled our little cabin with

hearty sounds of combustion. I was

curious about various items in the cockpit. Roy

shouted patronizing answers to my queries. I noticed

that he kept his feet flat on the floor. “Rudder

pedals are for sissies,” he explained. From time

to time, we threw barbs at each other. The fun might

last all the way across the desert. While

lighting up a filter-tip, Roy gestured for me to

take the control wheel in front of me. I shook my

head and pointed at the chart. "Are we

lost or what?" I asked. "Apple Valley Airport down there," said Roy.

"Nice runway, Roy. Why do you

suppose somebody painted `Barstow-Daggett' on it?" He banked the plane and squinted downward. "Did you leave your glasses home?" I asked. "Don’t need ‘em

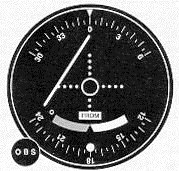

until I start taking lessons." A meter-like instrument on the control panel

made me curious.

Roy saw my quizzical expression. "Omni," he

hollered. "For

navigating." "Do you know how to use it?" I asked. "Too complicated." Roy looked at his watch and checked off a

point on our course.

Realizing he had an audience, he frowned at

the ground below then back at his chart. I grinned

at my wife in the back seat. "Roy is a fine pilot, Annie. He's going

to use his omni to

figure out where we are." "Not in front of the girls." Roy changed heading slightly, and we flew on

without talking.

I noticed the needle on the omni had come alive. There was

a knob on the instrument, and I wondered what it

did. I

resisted the temptation to touch anything. Roy was

watching me. "Be

my guest," he said. I turned the knob and the needle moved off

scale; back again and the needle centered. Next time

I caught Roy's eye, I gestured at the omni and shrugged. Roy

pointed at a blue circle on the chart. "Omni

station," he said. Around the rim of the blue circle were a set

of numbers. Examining

the omni on the panel,

I saw numbers just like them. They were

printed on a dial that moved when the knob was

turned. I

gazed at the desert below and thought for awhile. All at once, I got it: The

numbers match the chart. When the

needle is centered, the location of the plane is

given by that dial.

As we flew along, the needle appeared to

drift off center.

By re-centering it with the knob, I could

take a new reading from the dial. I noticed

that Roy had previously drawn lines on the chart

from the center of the blue circle, like spokes on a

wheel. These

pencil marks intersected our course line and gave us

our position. While we were just cruising along, I was

able to figure out how the omni

worked. The

thing is quite intuitive. Now, I was

hardly qualified as an airplane navigator, but I had

just learned something mighty interesting. I had no

idea how useful this knowledge would be. The very

next day. "You're right, Roy," I said, turning away. "It's too

complicated." This

is not the story about a Saturday in Las Vegas. I

faintly recall a swim in the hotel pool and the

dinner show.

Al Hurt, Pete Fountain, and a fellow named

Vaughn Meader doing

impressions of our President. Events in the sky

the following day all but scoured my memory. Roy barely touched his dinner. He

chain-smoked and complained that his stomach was

acting up again.

Sunday morning, my wife and I met Mildred for

a brunch in the hotel.

She told us that Roy had not been able to

sleep and was upstairs in their room. Annie and

I exchanged glances.

Later, Roy Barnes, pale and gaunt, joined us

in the lobby. "Them places," he

said, nodding toward the casino, "stay open all

night." The weather had changed. It was

cloudy when we arrived back at the Las Vegas airport

that Sunday afternoon.

Roy went to a phone booth to talk with the

weather people.

He was frowning more than usual when he

returned, muttering disagreeably about headwinds and

low clouds in the Los Angeles Basin. My wife smiled at Roy. “Why don’t we stay

another night?” she said. “We can just call up the

sitter.” Roy shook his head and took a long drag on

his cigarette.

"Las Vegas is a bad place to get stuck in." The four of us took our places in the plane

without speaking.

The little Cessna swerved along the taxiway. After

take-off, the plane seemed to be barely climbing. Our flight

path ran parallel to a highway. Cars and

trucks were passing us. I razzed

Roy about that but got nothing in return. He allowed

the plane to bank then jerked it back upright, first

this way then that. "Do you have any idea which way Santa Monica

is from here?" I asked,

just to get something going. Roy crushed out a cigarette, his second

since take-off.

"Downdrafts," he grunted. The air was smooth but murky, not clear like

the day before.

After the better part of an hour, Roy

announced that we had reached 6,000 feet. He turned

the plane toward the hills southwest of Las Vegas. By this

time the ground below us had become a brownish blur. We could

see clouds everywhere.

Rocky peaks stood above them. Our wives settled into conversation. There was

something unsettling about this flight so far. Not a bump

in the air, yet the plane felt like it was

meandering all over the sky. Roy's chart was still folded up in his lap. I reached

over and took it, half expecting him to object. He did not

even notice. I

examined the course line we had followed the

previous day. It

was not hard to figure out the general direction we

should be flying.

I pointed to the compass above the

windshield. Roy

looked up and squinted. Surprised,

he banked the plane into a turn. When

we reached a southwesterly heading, I made a

straight-ahead gesture with my hand. Once

again, I expected something from Roy to the effect

that I didn't know anything about this business. Instead,

he stared off into space, as if he were waiting for

further instructions. The sun shone through the windshield chasing

shadows across the panel whenever the plane turned. I noticed

we were still climbing. Our

altimeter read 9,000 feet. I asked

Roy how high he had planned to climb. His eyes

closed and opened twice. Suddenly,

he pushed the nose over, making us catch our breath. If I

didn't know better, I would say Roy was intoxicated. Roy's hand trembled noticeably when he

reached for the trim control. I thought

of the omni. The needle was moving, so I centered it with

the knob and read the dial. I looked

at the chart and saw those blue omni circles. I had not

learned the day before how to tune in different omni stations. One blue

circle on the chart had an angle that looked

reasonable for what I guessed was our location. Beside its

name, Boulder City, was

a box with the numerals 116.7. Sure

enough, they corresponded to a set of digits that

appeared on the face of the omni

instrument. Without

my noticing, Roy must have tuned in Boulder City the

day before. That

number, 116.7, had to be the frequency of the omni station on the ground. I began to

think that it would be a good idea to keep track of

our progress – and not just to pass the time,

either. We

could not see the ground at all. Constant droning of the engine and the

propeller blast made it difficult to hear the

conversation in the back seat. The sky

had become a pure blue canopy above the clouds. The ride

was utterly smooth.

It was as if the four of us were merely

spectators to a cloudy scene projected outside our

window. Roy looks worse by the minute. Questions

begin parading through my mind. Could it

be the altitude?

Should I suggest we turn back? Even if we

do that, could Roy find the airport in all these

clouds? How

might I broach the subject of returning? Roy seems

strangely docile right now. We are climbing again. And

banking left. "Are you all right, Roy?" No more questions. Get the

plane level. See

to Roy in a minute.

Try to feel the controls. "Whoa,

goddam it!" Now

pull. Hands

tightening on the control wheel. There had been warnings. Only they

were not real enough.

The emergency even now is not quite real. No

physical pain.

We are neither freezing nor burning up. No

gunshots or explosions. No threats

from predators.

If this is real, nature is no help. Yet the

four of us are surely going to die. Maybe it's already over for

Roy. "How are you doing, Paul?" my

wife asked. Her question is oddly

reassuring. I

want to answer, but there are crucial things to do

here. What

are they? Get

the wings level.

Push down.

Find the airport. What

direction? Get

to a doctor for Roy. Look for a hole in the clouds. What

airport, for crying out loud? Get

control first.

Mountains down there. Climbing

again, dammit!

Any airport.

What if he is dead?

I won't look at Roy again. "Trying to get the hang of

it, Annie." Now a pain begins. I'm almost

grateful. Fibers

in my stomach.

Not a sound from the back seat. Stay

level. With

each passing minute, the fibers get tighter. It's real. The handful of flying lessons that I had

taken back in 1957 were from the left seat, with

my left hand on the control wheel. In

retrospect, that might not seem to be significant,

but it was. Trying

to take over from the right seat six years later,

I found that what little tactile memory remained

was firmly committed to my left hand, and my right

hand became useless – or worse. Why are my hands fighting

each other? Maybe

if I let go with my right hand. That’s

better. I

remember something Roy told me yesterday: the

elevator forces in the control wheel ‑‑ I can

balance them out with the trim control. But I have

to let go with my left hand to reach it. Adjusting

up – no down. Grab

the control wheel again. Level the

wings. Let's see, when did we take

off? Was

it 1:30 or 2:30?

Trim some more. Wipe my left hand on my

trouser-leg. Where

was I? The

time. "What time is it?" I asked

over my shoulder.

The fibers are tightening. I do have

a watch on my left wrist, but I do not want to take

my eyes off those clouds ahead. "Quarter after three." Annie's voice is calm. I am not

ready for arithmetic.

Suffice it for now that we have been up here

for more than an hour.

It took us two hours to get to Las Vegas

yesterday. We

must be near the half-way point. We will

not go back. I

need help, though.

Maybe the radio. First,

trim. "Mildred, can you reach the

chart for me?" It had fallen on the floor. She folded

it to show the desert area southwest of Las Vegas. As she

handed it forward to me, I thanked her. I was able

to take a quick look into her eyes. Mildred

was crying. This

is craziness! Where

do I come off thinking I can pilot this goddam airplane. With a

corpse on board.

So this is what panic

feels like. The

two women in the back seat ‑‑ they must be paralyzed

with panic. It's

all over but the screaming. And the

crashing. Yet, no screaming, except

from inside me.

Am I the only one with stomach knotted up and

pulling tight?

Don't they know what the hell predicament

we're in? Mildred knows. Real

tears. She

handed me the chart, though, as if it were the

morning newspaper.

Sadness, grief, but no screaming. Annie must

know. If

I can see Mildred's tears, so can she. With Roy

gone, what hope do we have? Still,

when I asked my wife for the time, she answered with

no more concern than if we were tardy to a dinner

party. One

of them ought to be up here in the front

seat instead of me. No screaming ‑‑ and there is

no crashing going on here either. If those

women are not going to panic, maybe I won't either. It's craziness, all right,

but I'm going to fly Roy's one seventy‑two. Thanks,

Ladies. Let

go, fibers. The plane is level; now we

must get pointed in the right direction. Only short

glimpses at the chart.

Looks like a heading of about 200 degrees

should get us into the Los Angeles Basin. The

compass above the windshield is indicating “W.” That would

be 270 degrees.

So we turn left,

and ‑‑ oh, for crying out loud, why is the compass

swinging around that way? The

turn is stopped, but the compass is still swinging. Obviously

you can't read that thing while the plane is

turning. I

must nurse it around a few degrees at a time using

the sun as a guide. "Figure we ought to head

about two hundred degrees." I called

back over my shoulder, trying to sound confident. I can use

all the help I can get. Mildred

has flown with Roy and must know quite a lot. "What do

you think, Mildred?" Probably should be worried

about altitude, too.

Some long time has passed since I tried to

read the altimeter.

To do so, I have to look over to the left, by

Roy's knee. I

do not want to stir up those panicky fibers. Looking

over there is like peering into a coffin. Right this

minute, I wish I could just go off and think about

our situation for a while. Coming around to a heading of

220 degrees, I leveled the wings. Close

enough. When

I hand the chart back to Mildred, I'll just take one

look at the altimeter. Over 10,000 feet. Plenty

high. That

settles it. I

won't think about altitude for now. The radio. Here’s the

microphone, but what do I say? Better

know where we are first. Back to

the omni. I need to

find the next omni

station that might help us? The name

in the circle is Daggett. The frequency is 113.2. Mildred handed me the chart

again. "Paul,

I'd say that 210 degrees is the right direction." Just have to let that go for

now. I

want to tune in Daggett. Set the

frequency digits like so. "Hey, what

happened?" I can't help shouting. On the

face of the omni,

there's a red flag that says OFF. "Something wrong?" my wife

asks. "Plenty wrong!" I wish I were able to hold

things in better.

I’m going to guess: when we are too far away

from the omni station,

the OFF flag appears.

We are not as far along as I thought -- and

we have swung around toward the sun. Get back

on course. The

situation has improved. The plane

at least is level.

I don't care to think what we would do if

there were even the slightest turbulence. Thanks to

Mildred, we are on some kind of a course. Sooner or

later, we shall be close enough to Daggett to use

the omni. Roy Barnes is never far from

my mind. His

face was ghastly, last time I looked. The women

have succeeded in calming me down, though. My grip on

the control wheel is starting to relax. "What's that mountain up

ahead?” my wife asks, pointing through the

windshield. “Above the clouds, there.” She must

think I really can fly this thing. I never

told her the whole story about my solo flight six

years ago. It

was a near disaster. "San Bernardino range,

Annie." It

was a guess. "Better stay away from

Ontario, Paul."

Mildred's voice is wavering but strong. "Roy

told me once that a lot of airliners come in over

Ontario, on their way to Los Angeles International." Mildred's words, "Roy told me

once" sounds like something you might hear at a

funeral. Whether

intended or not, she has set our priorities. No more

thoughts about getting him to a doctor. Our own

survival is all that counts now. The engine is running

steadily with its own kind of confidence. If that

really is the San Bernardino range and we are still

northeast of Barstow, then we can see hundreds of

miles up here above the clouds. We won't

run into any mountains. "We're pretty far north of

Ontario, Mildred."

I forced myself to study the

altimeter. How

curious, we have climbed to over twelve thousand

feet. My knowledge of aviation that Sunday was elementary, mostly learned

from books. Hypoxia

produces physical symptoms that include headache,

nausea, and shortness of breath. Most

subtle – and probably worst for the safe conduct

of flight – is euphoria. The OFF flag on the omni has disappeared

sometime while I was not looking. It is

replaced by a flag that says TO. Center the

needle with the knob and read the dial. Look at

the chart. Compare. Something

is wrong. We

cannot possibly be where that dial says we are -- beyond

Daggett. We

have been in the air two hours, long enough to be

over the ocean.

Look down.

Nothing but clouds. San

Bernardino Mountains?

Shit! Those

are the islands off Santa Barbara! Look at the chart. There is

an omni station at

Ontario, tune in that one. It is

112.2 on the frequency digits. Turn the

knob, the needle centers, and the flag . . . the

flag says FROM.

The dial reads 20 degrees, which does put us

northeast of Ontario.

And over land.

I took a deep breath. That must

be the answer.

The flag must say FROM. Otherwise

the dial lies

to you. Probably

not the whole story, but it will do for now. Problem

solved. Annie is consoling Mildred. They are

talking in low tones.

I have no time for grieving. Most

important for now, I have to keep the plane pointed

on its course of 210 degrees. Roy went

out, doing what he loved best. Hell,

flying an airplane is something I have always

dreamed of doing, and here I am doing it. Seems I have figured out the

FROM flag on Roy's omni. Hooray for

that. Tune

in Daggett again.

Twist the knob all the way around until the

FROM flag appears.

There we are:

East and north of Daggett. Don't know

how far, but I know more about omnis

than I did yesterday.

Actually, we have not even come to

Daggett yet. Glad

I was able to keep that nonsense about being over

the ocean to myself.

We are not even half-way there. I forgot

about that long, slow climb and those "downdrafts."

Mildred is sobbing. Wish I

could help her as much as she has helped me. Not

possible. Annie

is doing her part. If Roy had a heart attack or

stroke, we should have tried to take him to a

hospital immediately.

Now that I realize how slow our progress has

been, I see that it would have been better to turn

back right after I got control of the plane. The

authorities will probably scold me for not turning

back. It

may not make sense to worry about what anybody

thinks. I

can't help it, though.

Thing is, I thought we

were farther along.

That ghastly look on Roy's face ‑‑ he was a

goner. I

shall have to live with the decision not to turn

back for the rest of my life. How long

will that be

anyway? Two hours now, or maybe

longer: I wonder how much gas we have left. They will

want to know on the radio. I

noticed the fuel gauges yesterday. They are

near the top of the cabin on either side of the

cockpit. The

one here on the right indicates less than half full. The one on

the left reads… the same. Another

problem. When I ease my grip on the

control wheel, the plane almost flies itself. Finally we

have passed Daggett and the town of Barstow

somewhere down there below the clouds. The air is

still smooth. Better

take another reading from the omni

station at Ontario.

The desert is behind us. According to the chart, there

are several airports nearby: San

Bernardino, Riverside.

But to get to them, we would have to be

"talked down" like in the movies. Meanwhile,

I am sitting up there at 12,000 feet solving

problems all by myself. At the time of the flight, radar was one

of my technical specialties, dating back to

research for the FAA in the earliest applications

of surveillance radar in air traffic control. Something

I knew well: ‘radar rooms’ were primitive as hell

in the early sixties. As incompetent as I was as a

pilot, I did not welcome the idea of anybody in a

radar room trying to rescue us. Studying the chart, I

concluded that we would soon be over the "Cucamonga

Wilderness Area."

If we are going to get talked down, why not

wait until we get to Santa Monica? After all,

Santa Monica was where we parked our cars. Our main worry must be

mountains. On

the chart, they are all around us. The ocean

looks much more inviting. What about

a landing into the ocean? I had

pleasant visions of flying off the edge of the coast

into the blue part of the chart and letting down

gradually to a soft splash. Like

diving into a pool.

Annie is a strong swimmer and so am I. We could

both help Mildred keep afloat if necessary. And it

doesn't matter about Roy. The water

will not even be cold, was my thought. Through no effort that I can

remember, the plane has been drifting down to lower

altitudes. Nearing

the San Fernando Valley, now, and flying at about

9,000 feet. The

engine is tending to business, keeping up its steady

drone all the way. While my eyes are fixed on

some parcel of clouds on the horizon, my mind's eye

gives substance to the coming scene: blind descent

through the overcast, violence of the water landing

as the wheels slam into the waves, sound of metal

crunching ‑‑ not like diving into a pool at all. With the

renewal of that clutching, fibrous pain in my

stomach, I know that reality is close at hand. “Diving

into a pool”? No

more wishful thinking, thank you. Our

problem is not running into a mountain, it will be

getting trapped inside a sinking airplane. Even up here in the clear

air, it has been a constant workout trying to keep

us going straight.

To avoid letting the plane bank itself into a

turn when you cannot see beyond the propeller, must

be a bitch! You

surely do not trust that stupid magnetic compass. What

can you

trust, “the seat of your pants”? Not

according to the book I read. Aviation books explain that for stable

flight inside a cloud, the pilot must rely on

gyroscopic indicators. Roy’s

panel had only one, the most rudimentary

gyro-instrument, Needle-and-Ball, which was a

subject not covered in my flying lessons six years

earlier. "There's a hole in the

clouds!" My

shout breaks a long silence. "See it?" Not a

hole, actually.

It’s the top of a mountain sticking up. Something

is glinting in the sun. According

to the last measurement I took on the omni dial, we should be

north of Pomona.

Seems like nearly another hour has gone by

since Daggett.

"Mount Wilson!

There’s the observatory?" That means we are quite far

north of where we ought to be. After probably three

hours, I have yet to try and contact anybody on the

ground. I

might be able to do that now, since I know exactly

where we are. They

will ask me how much gasoline we have left. Yesterday

we flew for about two hours. Per

agreement with Roy, I picked up the tab for

refilling the tanks in Las Vegas. They were

about half full.

So maybe we took off with enough fuel to fly

for about four hours.

So, I must tell people in the radar room that

we have an hour's worth of fuel left. Our

altitude ‑‑ they will want to know that too ‑‑ is

about 6,000 feet.

Been doing some more descending, I see. OK, radar room, I'm ready to

talk. I

picked up the microphone. Better

listen first. The

cabin speaker is over on the left-hand side of the

plane. Turn

the volume control up.

Coming from the Ontario omni

station is the voice of a man reading a weather

report. I

can barely understand his words. Wind

directions, cloud conditions, temperatures,

dew-points. Then,

"Long Beach closed; Torrance closed; Hawthorne

closed; Los Angeles closed; Santa Monica closed." "Santa Monica is closed!" The words

explode out of my mouth. We have to

go into the ocean.

We have

to. I hung up the microphone and

tuned in the Santa Monica omni

station. That's

110.8 on the frequency digits. The FROM

flag pops right up.

A clatter on the speaker. Now, a

recorded voice.

" . . . Santa Monica Omni . .

. Santa Monica Omni . . . " The dial reading from Santa

Monica is 30 degrees.

The fuel gauges now read "NO TAKE-OFF," less

than quarter tanks.

" . . . Santa Monica Omni . .

. Santa Monica Omni . . . " Can't talk to a goddam recording.

Suddenly Annie cries out,

"There's a big airplane down there!" Looking back over my right

shoulder, I can see Annie looking down. From her

shout, you might think we were about to have a

mid-air collision.

Banking the plane to the right, I can see a

break in the clouds.

Big airplane, all right, but it is not

flying. It’s

a Lockheed Constellation parked on the ground. Level the wings. Let that

compass settle down again. Quick look

at the chart. "That has to be the

Lockheed-Burbank Airport!" For the second time, I have a

confirmation of our location. Bless you,

omni! Should

I turn back and try to make it through that hole? Tilt

right, look again.

Gone. The hole

in the cloud has vanished. " . . . Santa Monica Omni . .

. Santa Monica Omni . . . " If I live to be a hundred

years old, I shall always remember the exact sound

of a flat, recorded voice, repeating those words

over and over as our little airplane cruised above

the clouds on a Sunday afternoon in April, 1963. Soon I must push the control

wheel forward to point us down into those clouds. The sun is

shining up here, and I do not want to leave this

clear blue sky.

No way to put it off, though. Since

we are north of where we ought to be, I must angle

to the left. Altimeter

now shows 5,000 feet.

Not much fuel left. Got to

hurry. The

hardest part is yet to come. The fibers

are back. The hills north of Santa

Monica are still ahead. Our only

hope is to head for the coastline and let down over

the water. I

need a "marker," something to tell me when we are

actually over the water. One more

look at the chart.

The omni again

‑‑ set up the omni dial

to read 270 degrees from Santa Monica. That marks

the coastline near Malibu. When the omni needle comes to the

middle, I will know ‑‑ this time for sure ‑‑ we have

passed the shoreline, even though I can't see it. Then I

must simply force

myself to take us down through the clouds. " . . . Santa Monica Omni . .

. Santa Monica Omni . . . " "Got your safety belts

fastened back there?" It is happening. The omni needle is moving toward

the center. The

decision is made.

Push the nose down. "Hang on. We are

going down." The plane is not banking

around like it did when I first took over. If I can

just relax a little and hold absolutely still… Picking

up speed. The

control wheel is getting stiff. Some

turbulence as we sink into the tops of the clouds. The pitch

of the engine is increasing. I want to

pull back. " . . . Santa Monica Omni . .

. Santa Monica Omni . . . " Suddenly, the horizon is

gone! For

a moment I am stunned, continuing to stare straight

ahead. It

is like barreling along inside a milk bottle. Cannot

allow the plane to tilt over into a turn. Cannot

allow myself to think about anything else. " . . . Santa Monica Omni . .

. Santa Monica Omni . . . " "Where's the airport?" "Don't talk to me now,

Annie." Banking left ‑‑ I feel it all

through my body.

Turn the control wheel to the right. Back to

the middle. Now

to the left again.

A few bumps in the air. Outside it

is becoming steadily darker. Seems

like the plane is turning right. The

compass says we are not turning at all. God, but

it feels

like we are turning right! Believe

the compass. Can't. Move wheel

to left, tighten my grip. No, now we

are definitely

turning left. The

compass has gone berserk. Bring it

back to the right again. The sky is getting darker. A glance

at the altimeter.

Zero thousands ‑‑ 500 feet! Only 500

feet above sea level.

Now blue-dark

from below. The

ocean! I

can see the water!

Right under us.

Rolling waves. " . . . Santa Monica Omni . .

. " I feel like letting out a war

whoop. Me

and this old one seventy-two ‑‑ we know each other. I can see

ahead and to the right. The

shoreline should be on the left. There it is, bank to the left. We did do some

turning in the clouds.

Pull up.

Not going to dive into that water yet if I

can help it. Low

on gas, but we can make it to the beach. Looks like

a mile away. Something is out of place! My mind is

racing. What? Going down

again, pull back.

No lower or we'll hit the water. " . . . Santa Monica Omni . .

. " In all this frantic activity,

as we came through the clouds, I was so totally

consumed, fighting the turns. Something

sure as hell is out of place. It’s Roy. He moved! Can't look at him right now. Got to

watch the shoreline.

Approaching at an angle to our flight path. Maybe one

quick look. No

shit. He is struggling to sit up. "Roy! You son of

a bitch! You’re

alive?" With a gasp, Mildred reaches

forward for Roy.

Looking out ahead, I see some big structures. Nose heavy

again. "Take

it easy, Mildred!"

Mildred is holding Roy's head

with both hands. "He must have passed out back

there," I exclaimed.

The structures at the

shoreline – that’s Pacific Ocean Park. Just like

yesterday ‑‑ except we are a damn sight lower now.

Sobbing from behind me; Annie is crying now. Finally. Got to know if Roy can take

over. "How is he, Mildred?" "Better get him to a doctor." That means it’s still up to

me. My

old friends, the gut fibers, are coming back in full

force. Pacific

Ocean Park is passing just below us. Heading

inland now over downtown Santa Monica. Forget the

gasoline; I think I'm going to find the airport. Sit there

and watch,

Roy, damn you! " . . . Santa Monica Omni . .

. " Houses and buildings. Power

poles and palm trees.

Too close, pull up. Mist on

the windshield.

Can't go any higher or we'll be back in those

clouds again. The

runway suddenly appears dead ahead. "There's

your airport, Annie!" We're almost on top of it. Turn

slightly. I

see the control tower.

Too fast!

How do we slow this thing down? The

beginning of the runway is right in front of us. We're at

an angle. Push

down and turn.

Almost lined up. Really low

now. " . . . Santa Monica Omni . .

. " Damn it, I can't reach the

throttle with my right hand without messing us up! "Roy, cut the power!" He struggles forward with

Mildred's help.

Roy's hand closes slowly on the throttle. "Now, Roy!" For hours, that little engine

has roared faithfully for us. Suddenly,

except for mild sputtering, it is quiet. Roy has

collapsed again back into his seat. Here comes the runway. This is

going to be interesting. Some faint

memory from more than six years ago has me heave

back on the control wheel. The forces

get weaker as the plane slows down. We sink

suddenly, quietly. Bang! The wheels

hit the pavement with a squeal and we bounced. The sunvisor drops in front of

my eyes. Push

it up. The

plane has gone crooked. Turn ‑‑

but the control wheel is useless. The front

wheel hits the ground and shudders. A short

stab at a rudder pedal. Veering to

the right. Other

pedal! A

cheer from the back seat. Slowing,

slowing. Off

the runway. Stopped. " . . . Santa Monica Omni . .

. Santa Monica Omni . . . "

Epilog The plane came to a stop on pavement beside

the runway. I

turned off the ignition. Mildred

continued to support Roy’s head from behind his

seat. I

opened the door on the right side of the plane,

climbed out, and held the door for my wife. She jumped

to the ground and flagged down a passing fuel truck

and told the driver to call an ambulance. I stood

under the wing and helped Mildred with Roy. We laid

him across the front seat. In a matter of minutes, we heard the siren

approaching the airport. Paramedics

loaded Roy onto a stretcher and lifted him into the

ambulance with Mildred by his side. His face

was covered by an oxygen mask. That was

the last time I would ever see Roy Barnes. Or so I

thought. My wife learned from Mildred that Roy was in

the hospital for several days. The

diagnosis was hypoglycemia. His

condition was aggravated by hypoxia and anemia, but

his heart was fine.

Weeks later, Mildred told us that their son

lived in Carlsbad near San Diego. She had a

new job there, and Roy was talking about setting up

a TV repair shop in Oceanside. With each passing day, I intended to call

Roy but felt too awkward. That

Sunday was an immense experience for me, comparable

perhaps to survival in mortal combat. I figured

Roy would be embarrassed if not apologetic. More than

once I picked up the phone, thinking to ease the

tension with a wise crack, “Thanks for letting me

fly your plane, Roy.”

But I never dialed his number. Then one

evening the phone rang. The voice

was familiar enough. “Got a gift for you, Paul.” “Bet I know what it is.” Back when we were working together, Roy

bragged about his charter subscription for Playboy. “Got all

twenty-four issues,” he had said. “Arlene

Dahl, Sophia Loren – starting with the December 1953

issue with Marilyn Monroe on the cover.” On the

phone Roy told me that he had found the collection

while packing for his move to Carlsbad. “Hell, you need them magazines more than I

do,” he said. We set a time and I dropped by his house in

Culver City. Roy

was waiting for me in the front yard. I shook

his hand firmly and looked long into his eyes. He seemed

quite robust, but I made no comments about his

health. I

noticed he was not smoking. We

exchanged small talk, with no mention of flying,

until Roy told me that he had sold Eight-Three

Charlie to a flying club. I said

that I was looking for a plane to buy, “With two omnis in it.” He nodded

without smiling.

Taking the gift from Roy seemed like the

best thing for both of us. I thanked

him, then made an excuse for quick departure. We loaded

the box in the trunk of my car and I started the

engine. Roy leaned into my open side window and

frowned. “That

was the worst goddam landing I ever seen.” |